Great artists who die young tend to get embalmed in their eras. The cliché is poetic and convenient at once: artists are supposed to channel the Zeitgeist anyway, and if there’s no other Zeit to complicate things, so much the better. Aubrey Beardsley, who died in 1898 at the age of 25, was a friend of Oscar Wilde and a protégé of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones. He looked like a waif and dressed like a dandy. He died of tuberculosis, the same disease that claimed Shelley, two-thirds of the Brontës, and Mimì from La Bohème. The whole, dizzying opera of 19th-century aestheticism seems to reach its finale in him.

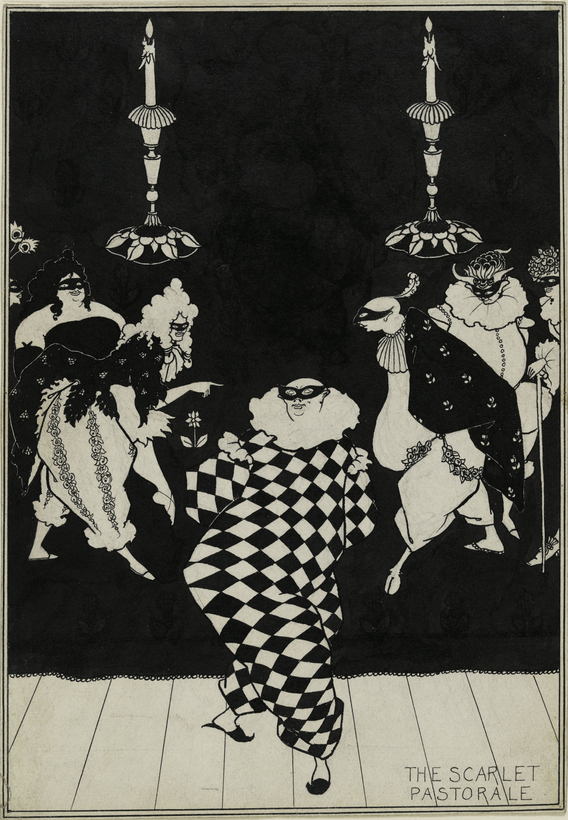

So why, then, do Beardsley’s drawings—the subject of a magnificent exhibition opening at the Musée d’Orsay next week—feel so contemporary? By attempting to put him into conversation with his peers, the curators have made him even more mysterious—an omnivore who wasn’t quite what he ate. Beardsley studied the Pre-Raphaelites, but his work has little of their misty sentimentalism. He admired Japanese prints, but bright colors tended to dilute his talents. His dense yet precise compositions bear a closer resemblance to 1960s album art than to anything made in his lifetime, which partly explains what he’s doing on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (second row from the top, far left).