John Lorimer, a reserve seaman, was “young, 19 and stupid” when in 1943 he volunteered for a “special and hazardous duty”. According to the advert, participants “must be able to swim”. He found himself on a mission from which he was not expected to return.

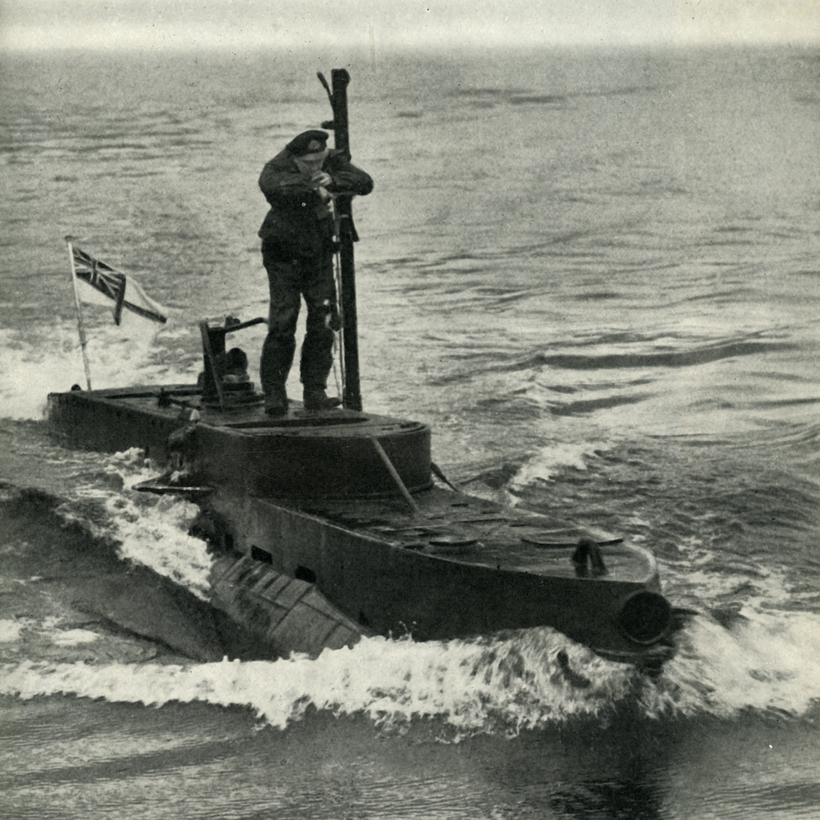

The objective of Operation Source was to use previously untried midget submarines (known as X-craft) to neutralise German warships in the waters of northern Norway. Among the targets was the heavily armed and seemingly invincible battleship Tirpitz, which had been posing a significant threat to the Arctic convoys. Winston Churchill had made her destruction a top priority. “She is the beast that would eat us,” he had declared in 1941. “If she were only crippled, the entire naval situation throughout the world would be altered.” It was easier said than done.