Unsound loans, new mortgage derivatives, and dishonest sales practices combine to pump a real-estate boom into a frenzied bubble that bursts with devastating consequences for the national economy: It could be a synopsis of the Michael Lewis best-seller The Big Short. But in Bubble in the Sun, veteran journalist Christopher Knowlton is describing instead the Jazz Age land rush that jump-started Florida’s development and proved, once again, that the mere idea of year-round summer can make otherwise sane people do extremely crazy things.

How crazy?

“Land sales caused small riots where crowds literally threw checks at the developers—in such numbers that they had to be collected in barrels,” Knowlton reports. “Seminole Beach was bought for $3 million one day, then sold three days later for $7.6 million. One Miami real estate office sold $34 million worth of real estate in a single morning.” Florida’s year-round population grew from fewer than 970,000 in 1920 to nearly 1.3 million in 1925, the year the now iconic towns of Coral Gables, Hialeah, and Boca Raton were added to the map.

Sunshine State of Mind

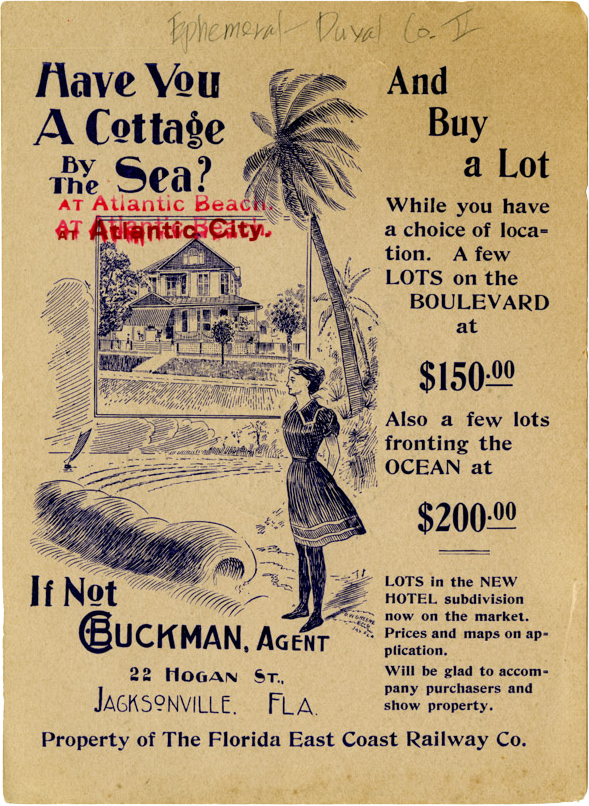

The sunshine obsession spread far and wide. “By the midtwenties,” Knowlton notes, “Wall Street was forming syndicates on a near daily basis to pool money” to buy into the land boom. Staid regional bankers recklessly pumped money into the bubble. Across the country, swampy lots were being deceptively sold to “buyers who had never set foot in Florida.” This wild national gullibility was captured by a young comic of the era: “I just got wonderful news from my real estate agent in Florida,” quipped Milton Berle. “They found land on my property.”

Carl Hiaasen could have cooked up Knowlton’s cast of characters. Robber baron Henry Flagler stars in the boom’s prequel, opening up railroad links and hotels that drew the wealthy to Palm Beach and, later, to Miami and Key West. But Knowlton’s main event belongs to less familiar giants such as George Merrick, the founder of Coral Gables; architect Addison Mizner, who helped create the Mar-a-Lago aesthetic; and Carl Fisher, who dreamed Miami Beach into existence on an unpromising sandbar. The writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas, the daughter of a Miami newspaper publisher, is woven into the tale, along with a collection of rogues ranging from Charles Ponzi to Al Capone.

Seminole Beach was bought for $3 million one day, then sold three days later for $7.6 million.

This crowded stage poses risks that Knowlton doesn’t entirely avoid. His pacing flags when the focus shifts to Douglas, whose great achievements as a crusading Everglades conservationist would come decades in the future, after the land-rush years. She simply doesn’t have enough to do to make her appearances compelling.

More troubling is a frustrating sin of omission. In the book’s opening pages, we hear briefly about a remarkable embargo imposed in 1925. Overwhelmed by the flow of building materials heading to South Florida, regional railroad owners simply refused to transport anything except fuel and perishables. “By year-end 1925, thousands of railroad cars were backed up in Jacksonville and other gateways to the state,” Knowlton reports. But he tells us nothing about the instigators of the embargo or of any efforts to get it lifted. It’s treated as if it were as much an “act of God” as the 1926 hurricane that played its own role in bursting the Florida bubble. In fact, according to one Depression-era account of the land boom, the state’s three largest railroads imposed various shipping restrictions in August 1925, expecting them to last no more than 10 days. A fear of shortages led to hoarding, while the embargo itself slowed construction of the new rail lines and warehouses needed to ease the logjam.

Going Bust

As it happened, the embargo dragged on for more than six months, with financial consequences that were disastrous. Millions in municipal bonds, sold on the assumption that buildings would rise on the land and that property taxes would rise with them, went into default. The banks that had bet their solvency on that future development failed, wiping out the savings of countless depositors. Knowlton concedes the embargo imposed a “forced recess” in the frenzy. As such, it surely deserved some of the attention devoted to Marjory Douglas.

Overwhelmed, regional railroad owners refused to transport anything except fuel and perishables to Florida.

Still, Knowlton delivers a captivating story, bubbling with colorful anecdotes and surprising research. As the triumphs and follies unfold, the narrative takes on a Canterbury Tales quality, drawing us into the turbulent lives of the real-estate kings, crime bosses, cynical hucksters, and romantic visionaries who laid the foundations of modern Florida.

Knowlton does not make a convincing case that the bubble’s collapse “brought on the Great Depression”—indeed, his text is far more careful and nuanced than his subtitle. But he does vividly remind us that the metabolism of regional real-estate markets can affect the health of the overall economy. That timely lesson, one we forget at our peril, has rarely been taught with such panache.

In his coda, Knowlton gives the last and lingering word to a realtor who lived through the doomed bubble: “As to why the boom stopped, the answer is very simple. We just ran out of suckers.” On reflection, the realtor added, “Did I say we ran out of suckers? That isn’t quite correct. We became the suckers.”

Diana B. Henriques is the author of The Wizard of Lies, on which the HBO movie was based, and, most recently, A First-Class Catastrophe