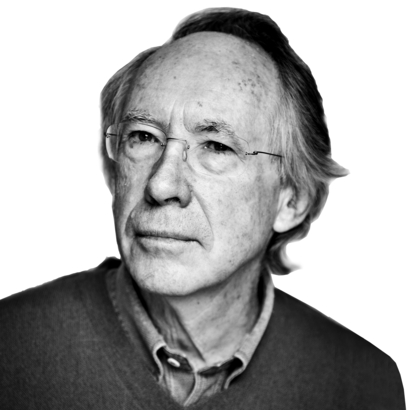

We Homo sapiens are living through the beginning of a great upheaval. There may be profound implications for photography.

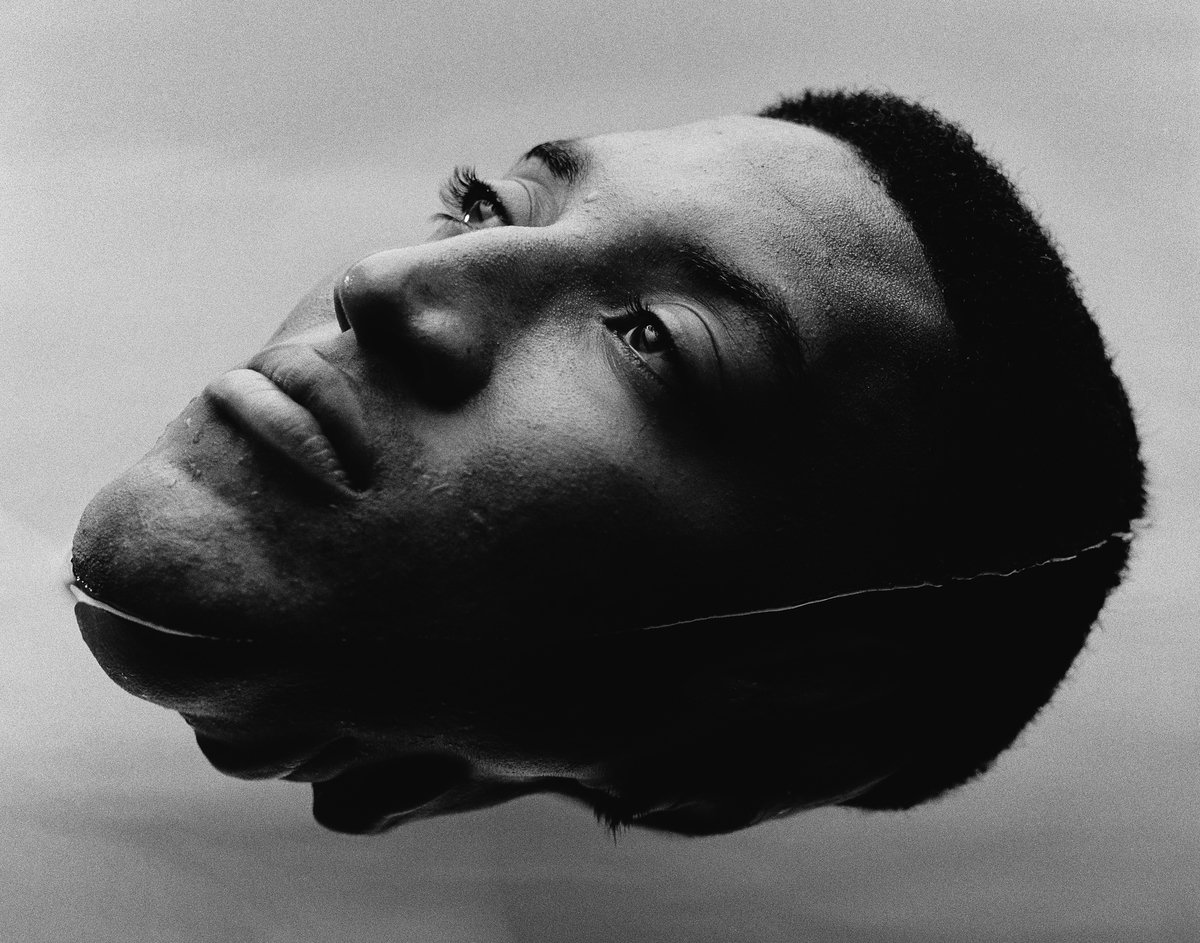

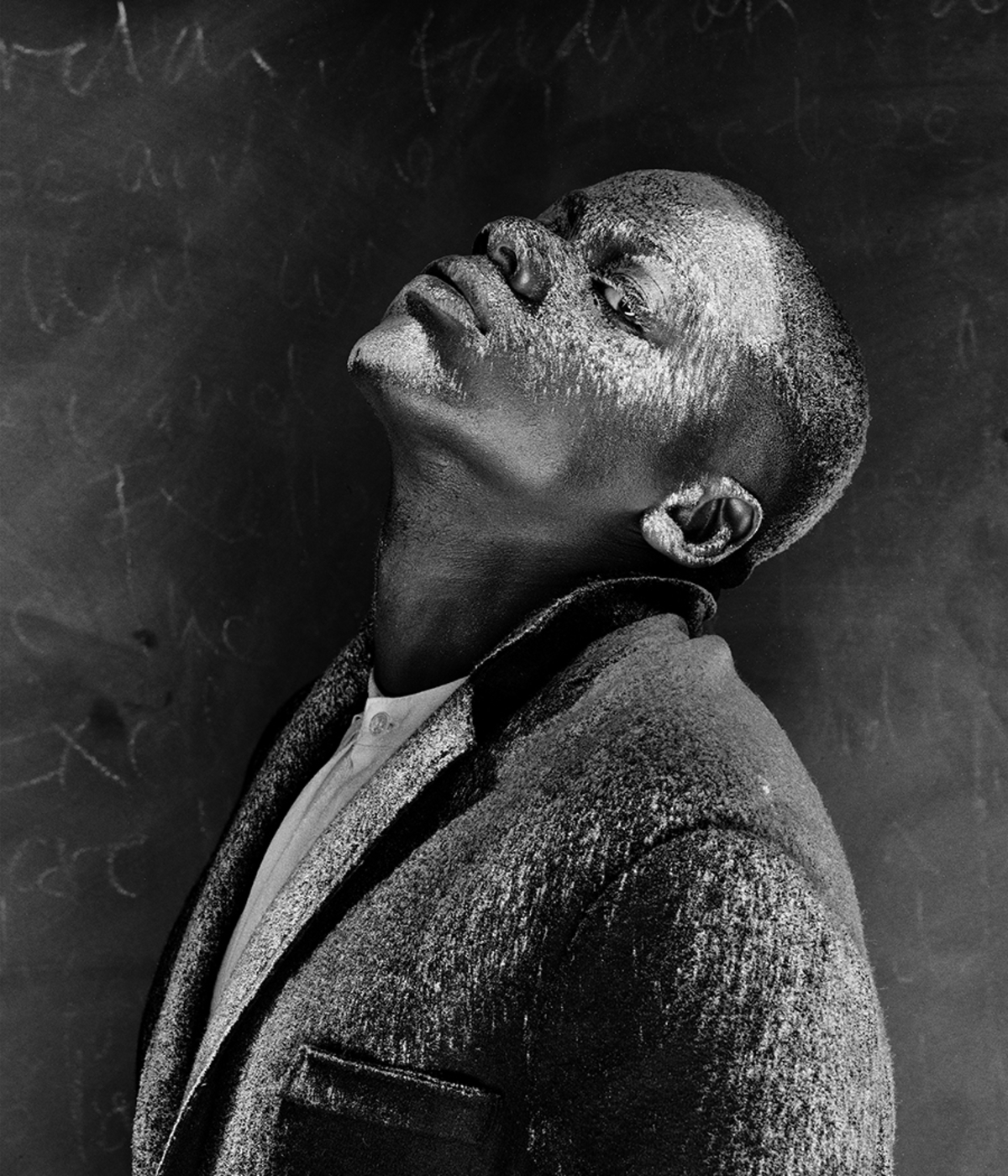

The past 10 years have seen a revolution in computer science. The age of artificial intelligence is now upon us. During the decades ahead, we will have to consider very carefully what it means to be human. When we look at each other through the lens of a camera, we might begin to see differently. More precious, perhaps, or endangered and transient.