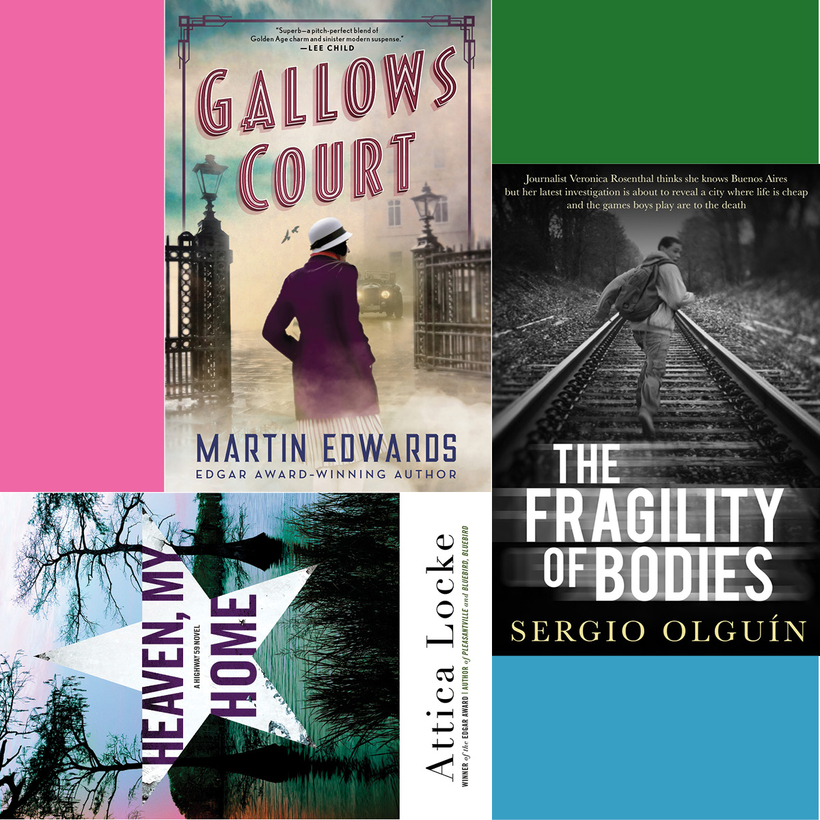

Heaven, My Home, the sequel to Attica Locke’s Edgar Award–winning Bluebird, Bluebird, is billed as a Highway 59 novel, announcing how integral that swath of East Texas is to its hero, Texas Ranger Darren Matthews. Being a black lawman in the heart of Trump’s America has its special set of challenges, which Matthews struggles with every day: the double takes provoked by his Stetson and his star, the ugly vibe that descends when he walks into a bar. When last we saw him, Matthews was not in good shape. He’d finessed a previous case in a way that left him open to both trouble and a bottle of bourbon.

This weighs on him as Heaven, My Homebegins, with the disappearance of a nine-year-old boy on a forbidding lake on the Texas-Louisiana border. Though the missing child is the son of an imprisoned white supremacist and no one seems too disturbed about his absence, Matthews is determined to find him for a variety of tangled reasons, some of them related to his own history with the father. He travels up Highway 59 to the antebellum town of Jefferson, where the boy’s wealthy grandmother rules with an iron checkbook behind the scenes, and, nearby, the impoverished Hopetown, where indigenous Indians coexist uneasily with the rest of the populace. As Matthews starts poking around in the towns’ discomfiting mix of trailer homes, Spanish moss–draped bayous, and Victorian mansions, he discovers that, in the margins, it’s more hell than heaven.