I hadn’t seen Hal’s death notice up north here in the woods by the sea when an e-mail came in from Graydon with the subject line “Hal Prince.”

Graydon:

“I don’t suppose your mom could write a short piece for us?”

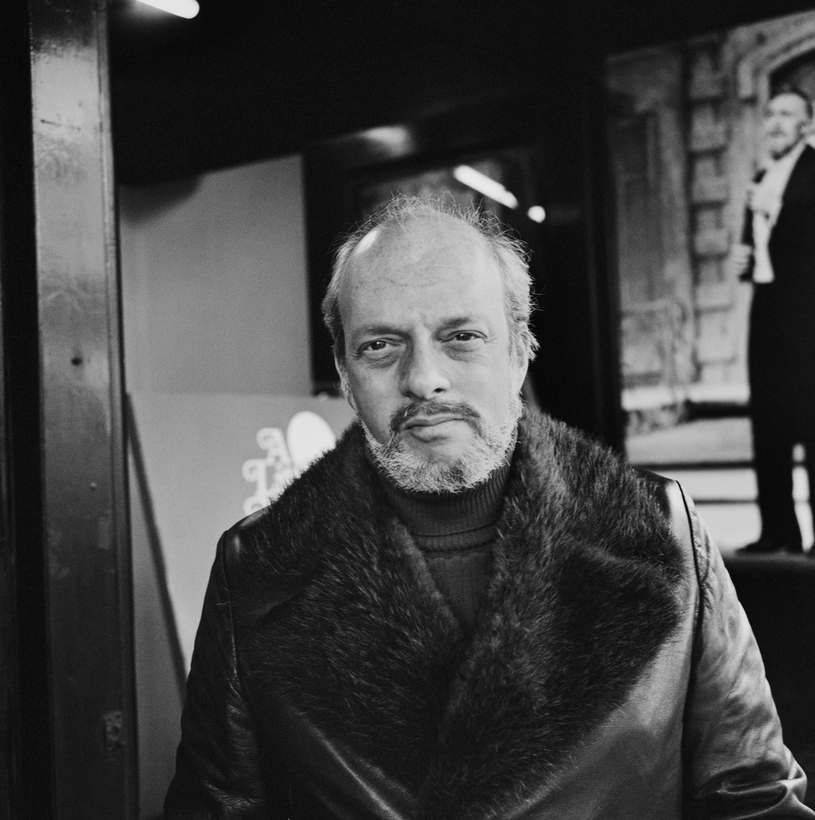

Hal Prince, as remembered by his longtime choreographer Pat Birch

I hadn’t seen Hal’s death notice up north here in the woods by the sea when an e-mail came in from Graydon with the subject line “Hal Prince.”

Graydon:

“I don’t suppose your mom could write a short piece for us?”