The artist Dóra Maurer, now 82, is celebrated in Hungary, but outside her native country most don’t know her name. Maurer cut her teeth during the Cold War 60s and 70s, and was a pioneer among Eastern Europe’s fledgling avant-garde. For much of that time she led a double life, as the system forced one to, producing figurative paintings in line with Soviet doctrine while going off the grid with experimental, conceptual, and minimalist films, photographs, prints, drawings, and reliefs—work that is, in a word, cerebral.

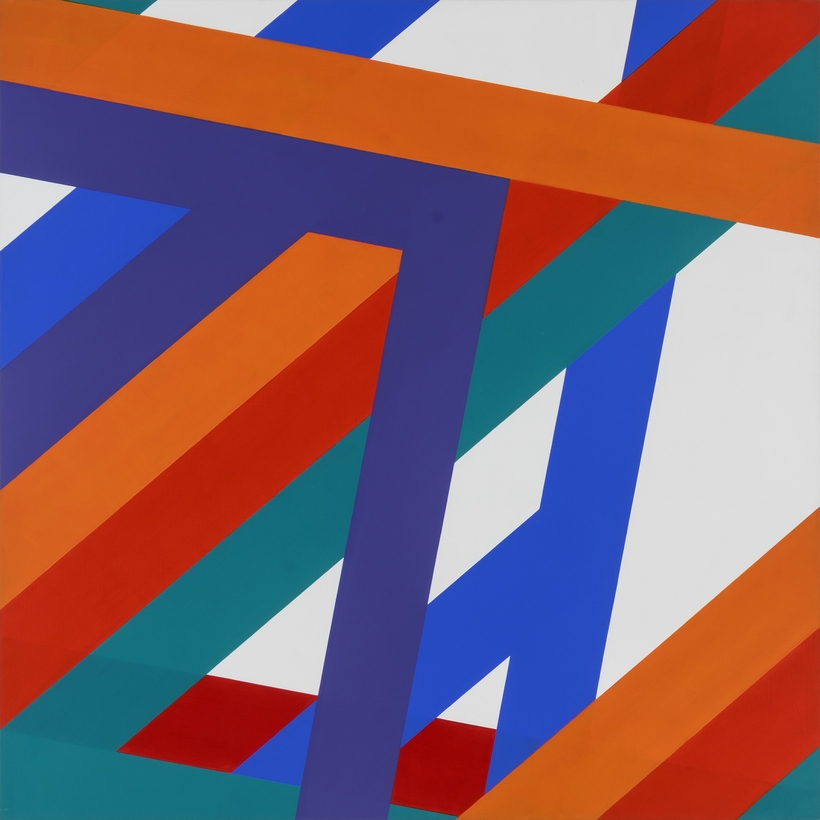

In 1970 (foreshadowing Ai Weiwei’s doomed Han-dynasty urn), Maurer dropped an aluminum printing plate from a fourth-floor balcony, simultaneously photographed the act, and then took an imprint from the battered plate, a turning point that shifted her studio practice from that of making images to the documentation of art-making. Additionally, since the 1980s, Maurer has been producing mathematically based, hard-edged geometric paintings of brightly colored stripes and warped planes—process-driven pictures and wall installations reminiscent of Op art, Barnett Newman, and Sol LeWitt, in which trompe l’oeil effects blur the illusionistic barriers between two and three dimensions.