Need a breather from December’s unrelenting holiday cheer, not to mention sugarplums? The Metropolitan Opera offers an ideal respite with its new production of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck, which premieres this coming week. A new Wozzeck is a highlight on any cultural calendar, and this iteration is designed and directed by the celebrated South African artist William Kentridge, whose recent work at the Met has included lively, image-soaked productions of two other 20th-century operatic cornerstones, Berg’s Lulu and Dmitri Shostakovich’s The Nose.

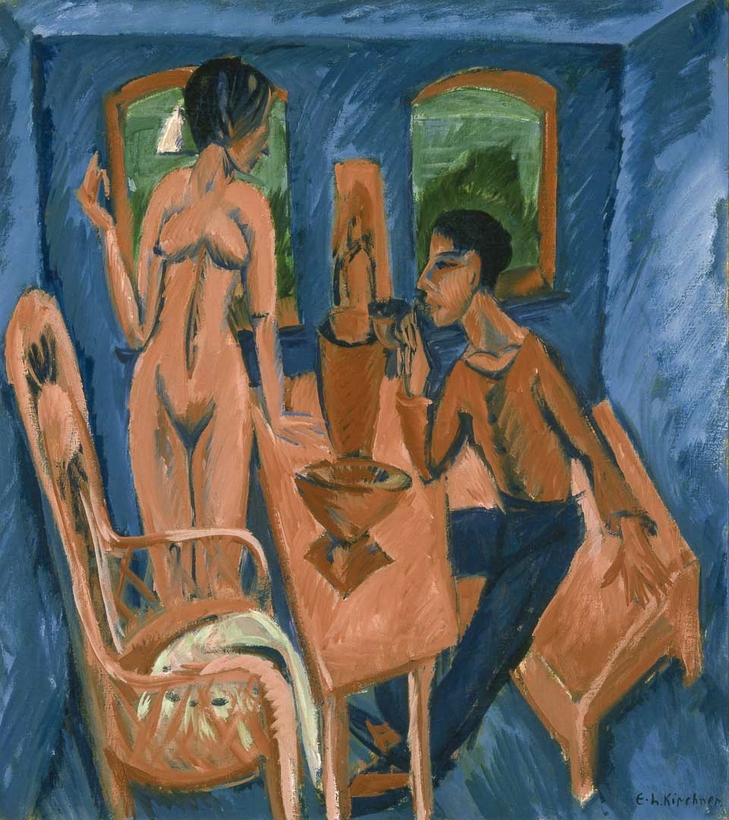

Running concurrently at the Neue Galerie, just across Central Park, is an essential exhibition of work by the German Expressionist painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. A major Kirchner retrospective coinciding with a new take on Wozzeck is not just a jackpot of Expressionism—Berg and Kirchner, an Austrian and a German, were direct contemporaries—it provides the perfect opportunity to consider the movement’s embodiment visually and musically. Berg’s opera can be heard as an aural corollary to Kirchner’s hyper-emotional, angst-ridden paintings. And like Berg, Kirchner reveled in dense, ecstatic, super-saturated colors that take possession of the senses.

Berg (along with his mentor, Arnold Schoenberg) extended the palette of musical composition to depict a disturbed inner world. By turning away from the prevailing musical language—tonality—he embraced jarring dissonance that mirrored unbalanced psychological states. If tonality is a musical G.P.S. that provides the listener with context—a feeling of security—atonality leaves the listener feeling lost and untethered, which is what the relentlessly victimized soldier Wozzeck experiences. Likewise, Kirchner’s atonal coloration of otherwise recognizable subjects elicits an equivalent sense of disorientation in the viewer.

Wozzeck is organized as a succession of brief scenes, none longer than 10 minutes, not unlike a guided gallery visit. Berg’s genius is that he forces us to experience this world not as passive viewers but through Wozzeck’s eyes and ears, through sensations that lead inexorably toward murder and suicide. Kirchner, in tragic real life, suffered spells of mental illness and madness; at age 58 he killed himself. A principal subject of Kirchner’s work was the metropolis without mercy—in other words, modern man’s inhumane treatment of his fellow man—and this was Berg’s subject, too. —Neal Goren