After the bombs fell on Berlin’s zoo, the rumors flew. Escaped elephants were said to be promenading along the Kurfürstendamm, the city’s Champs-Élysées. Somebody spotted a tiger eating cake in what remained of the Café Josty.

Katharina Heinroth, the young wife of the aquarium’s director, was tending to wounded Berliners in the zoo’s air-raid shelter—her husband, Oskar, among them—when the Russian soldiers arrived. They raped her. She managed to drag Oskar home to die, burying him in a coffin that zoo carpenters had cobbled together from the doors of bombed-out buildings. The first woman to receive a doctorate at the University of Breslau’s Zoological Institute, Heinroth earned the nickname “Katharina die Einzige”—the one and only Katharina. Unshakable, she took charge of the zoo after its Nazi director, Lutz Heck, a close friend of Göring’s, fled Berlin on a bicycle.

Somebody spotted a tiger eating cake in what remained

of the Café Josty.

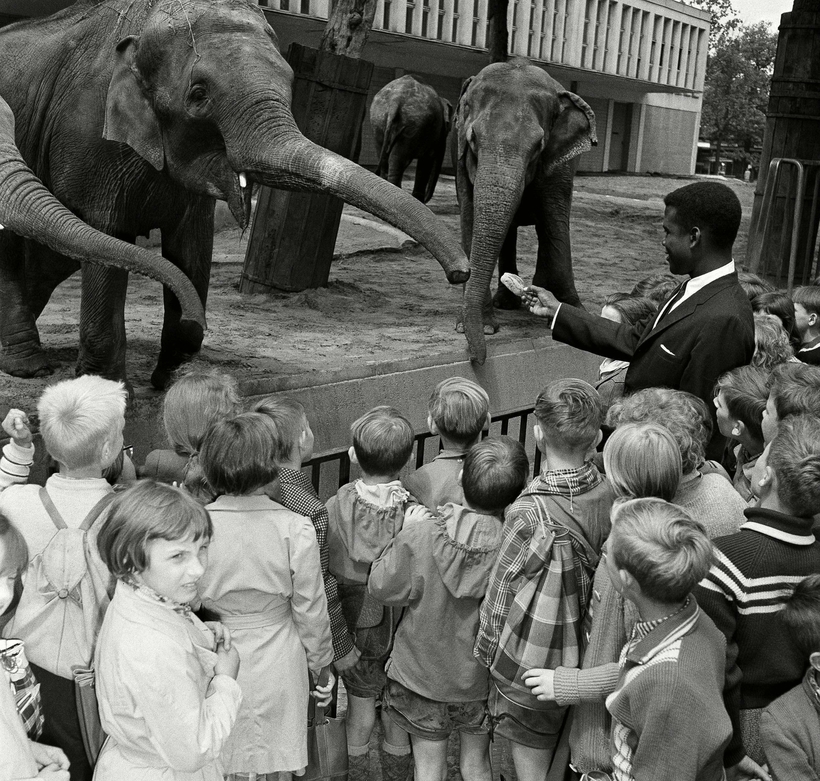

Germans go to zoos the way the French go on strike: frequently. When Knautschke, the Berlin Zoo’s popular hippo, orphaned by the bombings, died in 1988, his death briefly united in grief a divided Germany. As J. W. Mohnhaupt writes in The Zookeepers’ War (translated from the German by Shelley Frisch), some 16 million East Germans a year visited their country’s zoos during the 80s—as many zoo-goers as there were East Germans. In West Berlin, the Berlin Zoo and its aquarium recorded three million visitors annually, half again as many people as there were West Berliners, only 1 in 10 of them tourists.

My family and I became regulars when we lived in Berlin for several years, not long ago. Every weekend I biked or walked with our younger son the few blocks from our apartment, just off the Kurfürstendamm, to check in on the mandarin fish and the lions. Rebuilt after the war, the historic aquarium became our retreat in winter, the zoo our harbinger of spring. We would pass beneath the pagoda roof of the reconstructed elephant gate, where I measured our son’s changing height, and the passage of the years, against the sandstone pillars.

Heinrich vs. Heinz-Georg

The Zookeepers’ War is a charming account of a decades-long rivalry between Heinrich Dathe, the dour, scholarly, former Nazi zoologist and educator who founded and directed East Berlin’s zoo, called the Tierpark, and Heinz-Georg Klös, the opportunistic, insecure veterinarian turned administrator who replaced Katharina Heinroth as head of the West Berlin zoo during the mid-50s. German officials, it turned out, couldn’t abide a woman in charge. Among those who bemoaned the zoo under Heinroth was Heck, still alive, unbowed, and re-settled in Wiesbaden.

“In a sense, West and East Berlin were themselves two zoos,” as Mieke Roscher, a German scholar, points out in the book. “The feeling of being enclosed within a border was palpable everywhere.” The zoos were microcosms of postwar Germany, subsumed, like everything else during the Cold War, into the ideological struggle. Whether the Tierpark or the Berlin Zoo scored the tapir or the Chinese panda, or built the biggest rhinoceros house, or attracted the most visitors per year, counted as a victory for capitalism or socialism. The competition only heightened public interest in the zoos.

As it happened, a rare détente involved those sandstone pillars, Mohnhaupt writes. The original elephant gate, from 1899, destroyed during the war, had been quarried in what became East Germany. When Klös decided to reconstruct the gate in the 80s, two West German contractors bid on the job. They wanted to charge a fortune. The director of the East German quarry then approached Klös, offering to rebuild the gate himself for half the price. Facing a dilemma, Klös went straight to the West German president, Berlin’s former mayor Richard von Weizsäcker. The president blessed the deal with the East Germans. The new gate became a victory for both capitalist thrift and socialist pluck.

“In a sense, West and East Berlin were themselves two zoos.”

The zoo battle seems quaint today. West Berlin won. But the Tierpark comes across in the book as an endearing underdog, a sprawling, bootstrap institution, born from Dathe’s sheer determination and zoological prestige. The Tierpark was where my wife took our two boys on what seemed like endless walks through a sparsely appointed preserve bounded by wide Stalinist avenues and faceless housing blocks on the edge of the city, a survivor of the socialist dream.

The Zookeepers’ War is leavened with stories beyond Berlin. Among the bit players weaving in and out of the book is Martin Stummer, a Bavarian adventurer who began trapping animals in Ecuador, supplied Klös with South American deer, and who, Mohnhaupt writes, ended up in the Philippines as the king of a small island. One wishes to know more about him. Not all the minor figures on whom Mohnhaupt periodically dotes are quite so colorful. Dathe and Klös are hardly Shakespearean characters, either, but as frenemies for nearly half a century, they encapsulate the larger saga of the great city, the era, and a world in conflict.

As for Heinroth, she died just before the fall of the Wall, leaving behind a biography of Oskar. Not far from the last apartment where my family and I lived, there is an elementary school named after her. She is buried next to her husband, on the grounds of the Berlin Zoo.

Michael Kimmelman is working on a book about Notre-Dame in Paris