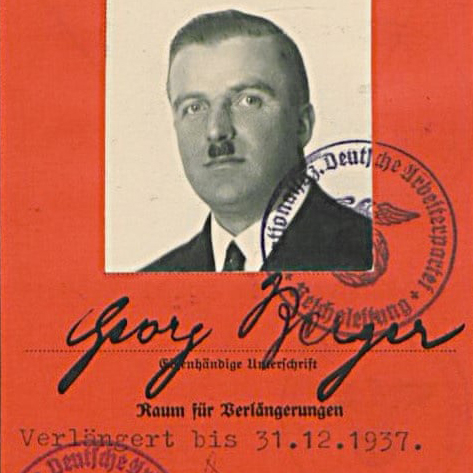

It was an inspirational tale: after watching the horror of the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938, a German man tore up his Nazi party membership card in protest and turned against the regime.

His Christian-based principles led to him being hounded by the Gestapo, sent off briefly to Dachau concentration camp and eventually dispatched to the eastern front.