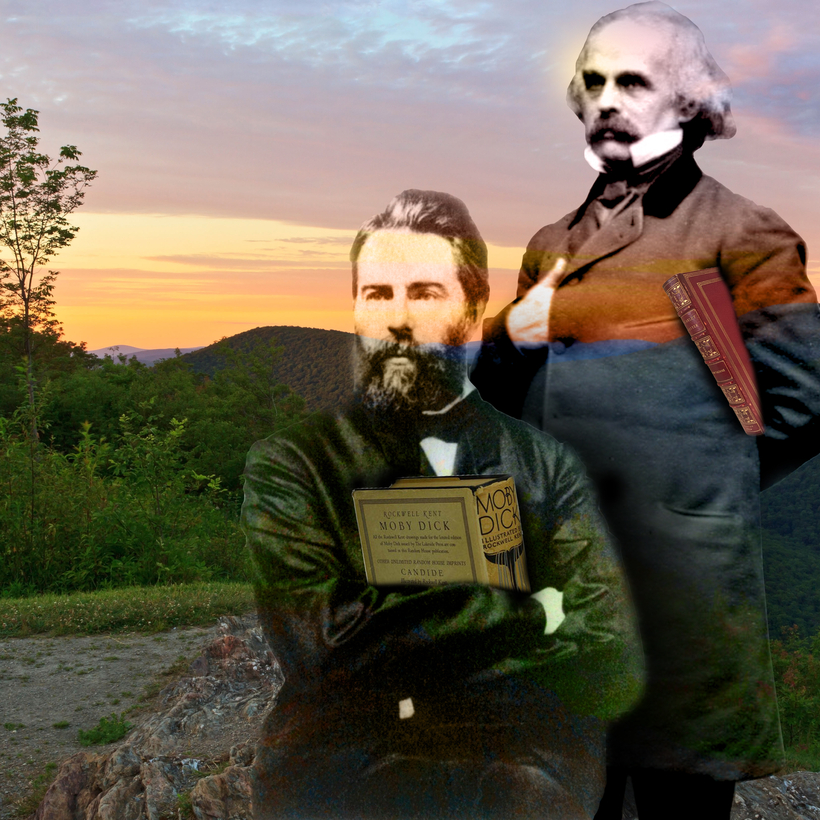

“You are about to celebrate a picnic that changed the course of American literature,” announced Gordon Hyatt, a gentlemanly former CBS documentary producer who was raised in the Berkshires and who developed a strong interest in local cultural history. He addressed us from atop a picnic table at the base of Monument Mountain, a lowish peak that flanks the west side of Route 7 between Great Barrington and Stockbridge, Massachusetts. There were around 20 of us gathered to mark the anniversary of a simple but extraordinary walk. On August 5, 1850, Herman Melville, summering at his late uncle’s estate in nearby Pittsfield while writing a whaling adventure, met Nathaniel Hawthorne, who, fresh off the success of The Scarlet Letter, was booted from his job in the Salem Custom House and headed west to Lenox with his wife and toddler. The occasion launched one of the most momentous and speculated-upon friendships in literary history.

I was there on a blistering Sunday morning, three days after Melville’s 200th birthday. A couple of years ago I picked up a novel, Mark Beauregard’s The Whale: A Love Story, which posits an amorous relationship between Melville and Hawthorne, 15 years his senior, ignited that day in the Berkshires, where the book, which uses both writers’ actual words in a fictionalized context, begins. Turns out, the likelihood of a Melville-Hawthorne affair has been debated openly in the academy since the 1950s, even though it was not much discussed in the broader culture (not all that surprising in a country where same-sex marriage was legalized only in 2015). “Read what’s on the page in Melville’s books and letters and Hawthorne’s journals,” says Beauregard. “It’s very clear what’s going on.” Particularly, he notes, in Moby Dick,a draft of which the married Melville was immersed in the day the two men clicked. It is, however, generally accepted that—with or without consummation—the friendship had a massive influence on Melville’s work.