The trouble with public houses is that the public is let in. For exclusivity purposes — and the chance to choose your own riff-raff — there are the London gentlemen’s clubs, 400 of them in the West End in Edwardian times, although fewer than 50 survive today.

When I was a younger man I used to go on a regular club crawl with the venerable wine writer Cyril Ray. Drinks at the Lansdowne and the Athenaeum, lunch at Brooks’s, more drinks at White’s, dinner at the Reform. The Arts Club, in Dover Street, came into it somewhere. I would end the day in a shopping trolley at Paddington station, wearing a kettle on my head.

A League of Their Own

As Stephen Hoare shows in his sober study of these institutions, clubland represents “a sedate experience based on shared British values”. Most of the clubs are housed in beautiful, solid 18th and 19th-century buildings, usually by James Wyatt, Charles Barry or Alfred Waterhouse. The Reform, for example, an Italianate palazzo in Pall Mall, was constructed in 1841 at a cost of £84,000 and is a popular film location — Phileas Fogg, in Jules Verne’s book and David Niven’s performance, set off from there to circumnavigate the globe in 80 days.

A typical ostentatious club is flanked by cast-iron gas lamps. There are Doric pillars, ticker-tape machines to send dispatches about remote wars, and vast staircases. Once at the Garrick with a friend we watched as the Pickwickian figure of Kingsley Amis fell in slow motion down the stairs, landed at our feet, got up without a qualm and went off to order another single malt. We laughed.

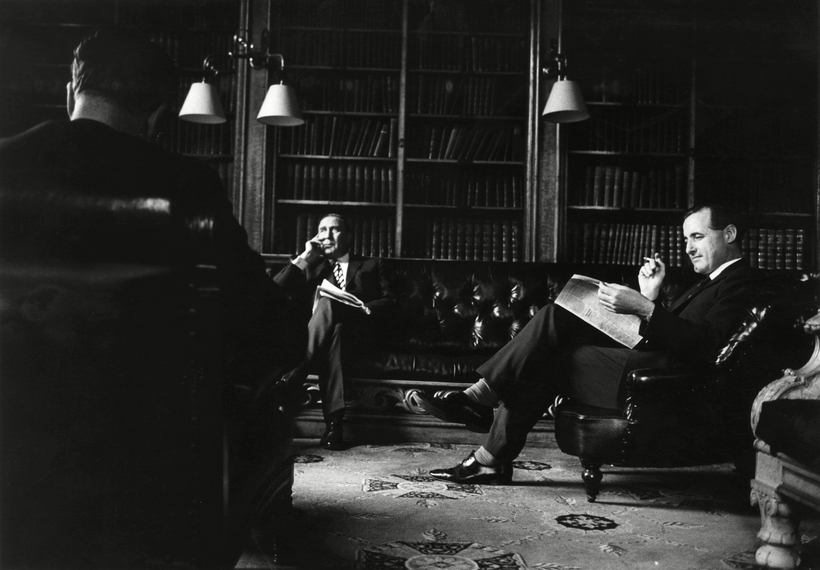

As Hoare says: “Being a clubman conferred a sense of identity. It meant that you were a member of a certain tribe. It was an outward sign of success and acceptance into society.” The club is a symbol and embodiment of the establishment; these “palaces of power” are actually the corridors of power. They were also symbols of political allegiance. At the beginning of the 18th century Whig supporters of the Hanoverian dynasty patronised the St James’s Coffee-House (its members were the nucleus of Brooks’s), Jacobites favoured the Cocoa Tree (which closed in 1932) and the Tories Ozinda’s.

Once at the Garrick we watched as Kingsley Amis fell down the stairs, got up without a qualm and went off to order another single malt. We laughed.

The institutions grew out of the bustling coffee-house tradition — coffee being strong and bitter and “not to female tastes”. The gentlemen would sit cheek by jowl, engaging in rowdy debate and making wagers, such as one made in White’s that a manservant “could breathe unaided underwater for 12 hours” (the bet was lost and the servant drowned). Brooks’s Betting Book records that in 1785 “Ld Cholmondeley has given two guineas to Ld Derby to receive 500 Gns [guineas] whenever his lordship f***s a woman in a balloon one thousand yards from the Earth.” Did his lordship join the 1,000-yard high club? The outcome of the bet is not recorded.

The Regency bucks and junior officers, who had seen action in the Napoleonic Wars, had names straight out of PG Wodehouse: “Teapot” Crawfurd, “Poodle” Byng, “Tiger” Somerset, “Kangaroo” Cooke and Sir Lumley “Skiffy” Skeffington. The backrooms of the Cocoa Tree and the Kit-Cat Club, whose members included the writers Joseph Addison, Richard Steele and William Congreve, were available for private hire. Dinner parties with fine wines were held. Portraits were put on display. Then entrance fees were levied at the old coffee houses and the modern idea of a private club came into being, with steep joining charges and annual subscriptions.

Comfort Zone

Then, as now, the area chosen was around St James’s, a district of grand mansions, expensive shops, wine merchants, hatters and bespoke tailors. The clubs “acted as a vast clearing house for information, rather like today’s social media”. There was great variety in the type of clubs you could join. One wag in his book, A Compleat and Humorous Account of All the Remarkable Clubs and Societies in the City of London and Westminster, claimed that there was a Farting Club, whose members ate cabbage and onions and “poison[ed] the neighbouring Air with their unsavoury Crepitations”.

Not to be confused with that “bumfiddling” institution was the Athenaeum, “a temple to culture, science and the arts, especially poetry and literature”. Founded in 1824, it was dedicated to the Greek goddess of wisdom, Pallas Athene. Its original annual subscription was six guineas (£350 in today’s money). Taking the shine off the Athenaeum somewhat is that Jimmy Savile was an enthusiastic member. And talking of the naughty step, in 1951 Guy Burgess spent his last night in Britain before defecting to Russia at the Reform.

“Being a clubman conferred a sense of identity. It meant that you were a member of a certain tribe.”

Clubs were at their peak as emblems of empire. The Travellers, the Oriental, the Royal Over-Seas League, the East India, where members, people who had played roles in the Raj, could eat chicken curry and mulligatawny paste; the officers’ clubs, such as the Army and Navy, the Cavalry and Guards, the Naval and Military (the “In and Out” ) — these were homes-from-home for imperial administrators, senior civil servants, government ministers, adjutants and retired generals.

A decline set in after the First World War, however, when a generation of members or potential members was slaughtered. Between the wars clubland went further out of favour as Edward, Prince of Wales, led the fashion for nightclubs, jazz and dancing to gramophone records. Also, as we see in the antics of Evelyn Waugh’s characters, the sexes wanted to mix.

Survival of the Classiest

During the Second World War, however, clubs were a cheaper option than hotels, and rooms were booked up months in advance by overseas delegations, Whitehall politicians and military personnel. It is horrifying to learn that at the Army and Navy Club, “vintage port could only be served at luncheon and then only on two days of the week. Members were limited to 2 quarts of champagne and 2 quarts of French or German wines in each calendar month.”

There were also fewer servants, owing to conscription, and Italian cooks were interned as enemy aliens. Many clubs were victims of the Blitz. In the postwar period there were closures, demolitions and amalgamations. If they have survived it is because, Hoare argues, they are “a symbol of good taste” and “kept faith with the past” by retaining a hint of Edwardian formality. For instance, the 600 members of the exclusive Pratt’s include six knights of the garter.

There are problems. Clubs are still mainly male enclaves. The first recorded example of a club admitting a woman as a guest was in 1863, when Princess Alexandra, the wife of the Prince of Wales, visited the Travellers; it led to the club building a separate room for the reception of ladies. It remains men only, as do the Garrick, White’s, Brooks’s, Boodle’s and the East India. This is silly, as is the sixth-form common room atmosphere I have encountered with the self-important committees.

When Hoare says clubland represents “the need for an identity in a whirling city”, does he mean clubland is an oasis of white upper-middle-class supremacy? Those buffers you see on the steps of their Pall Mall bastions, swaying and blinking at the light — they must think they are General Gordon at Khartoum.