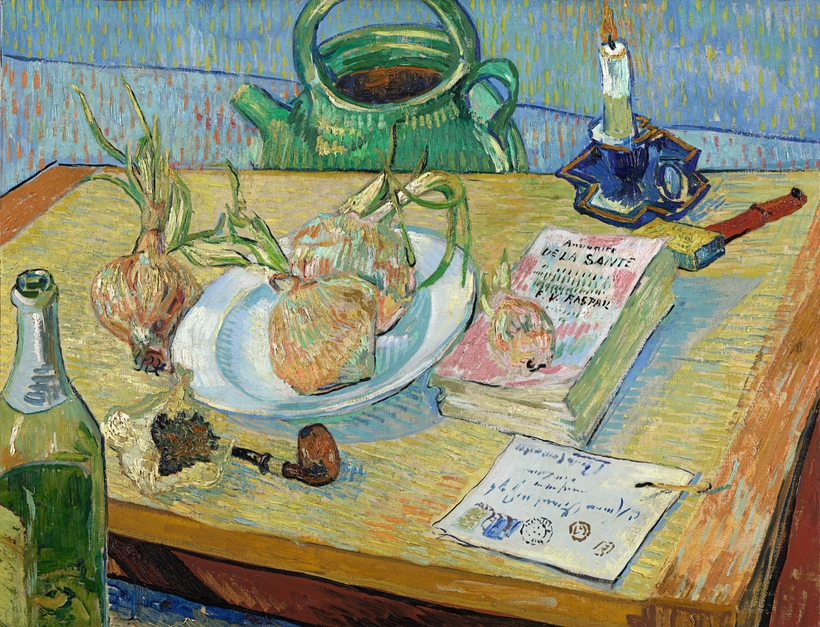

Van Gogh’s still lifes are never still. Heightened color and visceral drawing wrestle, interweave, and beautifully assault us. We ride the Dutchman’s writhing brushstrokes, which heave us as if on roiling seas, shower us like fireworks. Van Gogh knew the punch his pictures packed. “You will receive a big still life of potatoes,” he wrote to his brother, Theo, in 1885, going on to explain how he tried to get palpable mass, body, “to express the material in such a way that they become heavy, solid lumps—which would hurt you if they were thrown at you, for instance.”

The Museum Barberini’s “Van Gogh: Still Lifes,” the first Van Gogh survey, surprisingly, to tackle this most humble of painting genres, does not include that early still life of potatoes among the 27 paintings in Potsdam. But on view will be other early, earthen-hued pictures, such as Still Life with Apples and Pumpkins, a bountiful, rotund gathering suggesting a battery of cannonballs; the subterranean Birds’ Nests, like tunneling through thickened brambles, crowns of thorns; and his first stab at the genre, 1881’s Still Life with Cabbage and Clogs. These weighty, monochromatic pictures were painted before Van Gogh internalized French Impressionism’s atomized light and the flat patterning of Japanese prints. At the time he was still under the spell of Rembrandt and Jean-François Millet.