“I’m not the bloody queen!”

Jane Tennison in Prime Suspect

She had come to christen a ship.

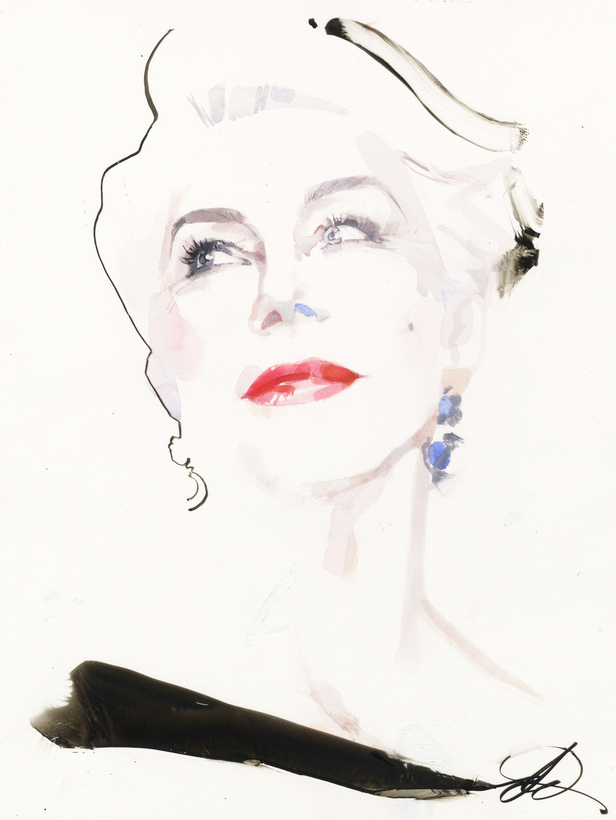

Helen Mirren brings something special to every performance. But for HBO’s Catherine the Great, she also draws on her own White Russian roots

Jane Tennison in Prime Suspect

She had come to christen a ship.