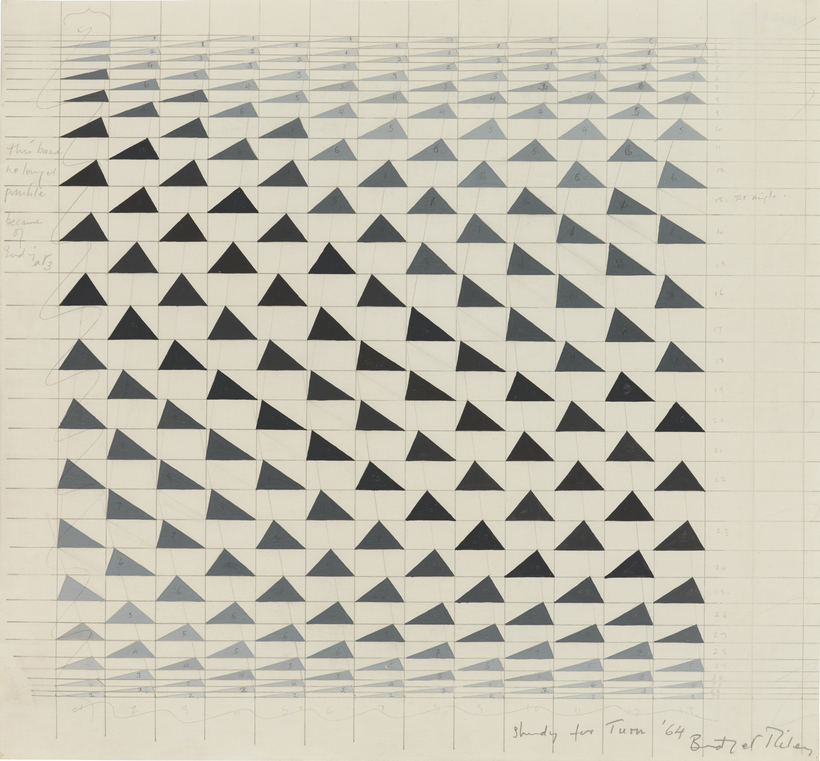

Op art got a bad name almost as soon as it got a name. The year was 1964 and Time magazine—or Donald Judd (sources vary)—coined the term to refer to a brand of hard-edged abstract painting that often flirted with optical illusion. At its slickest, op art’s trippy, eye-tickling effects were psychedelic-adjacent, easily transferable to dorm-room posters and throw-pillow fabrics—abstraction’s equivalent to a Happy Meal. But some practitioners probed deeper, finding sublimity in the genre’s rhythmic, sometimes warped geometries, and none more so than Bridget Riley, the 88-year-old English painter who is the subject of a retrospective opening this week at the Hayward Gallery, in London’s Southbank Centre. (The show, billed as the artist’s most extensive to date, originated this summer at the Royal Scottish Academy, in Edinburgh.)

Some practitioners probed deeper, none more so than Bridget Riley.

Like Mondrian, a major influence, Riley is an artist whose work demands to be seen en masse. Her paintings find meaning in conversation with one another and in what those conversations reveal about Riley’s obsessions and ways of seeing. Not that her big, bold canvases can’t dazzle solo. “More than anything else I want my paintings to exist on their own terms,” she wrote in the essay “The Pleasures of Sight,” in 1984. “That is to say they must stealthily engage and disarm you. There the paintings hang, deceptively simple—telling no tales as it were—resisting, in a well-behaved way, all attempts to be questioned, probed or stared at and then, for all those with open eyes, serenely disclosing some intimations of the splendours to which pure sight alone has the key.”