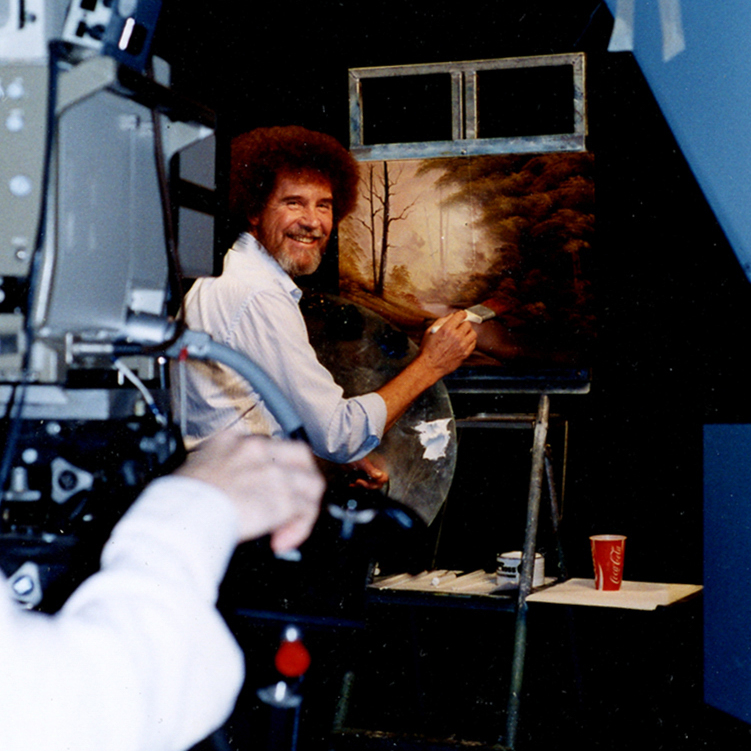

Cometh the hour, cometh the mediocre painter: Churchill in 1940, Bob Ross today. Twenty-five years after his death, the big-haired American art tutor is back, teaching us how to knock up a landscape in oils in 30 minutes with just house painter’s bristles and all the Zen in the universe.

For BBC Four, which since April has nightly aired 30-year-old repeats of The Joy of Painting, Ross has brought nothing but joy. The other week his art class was its second most watched program, bettering by more than 100,000 viewers a big new documentary about Beethoven. As a token of its regard, the channel followed Tuesday night’s The Joy of Painting with a 2011 documentary, Bob Ross: the Happy Painter, a celebration of the air force sergeant turned paint whisperer who has taught millions to paint (sort of) and brought half-hours of well-being to many more.