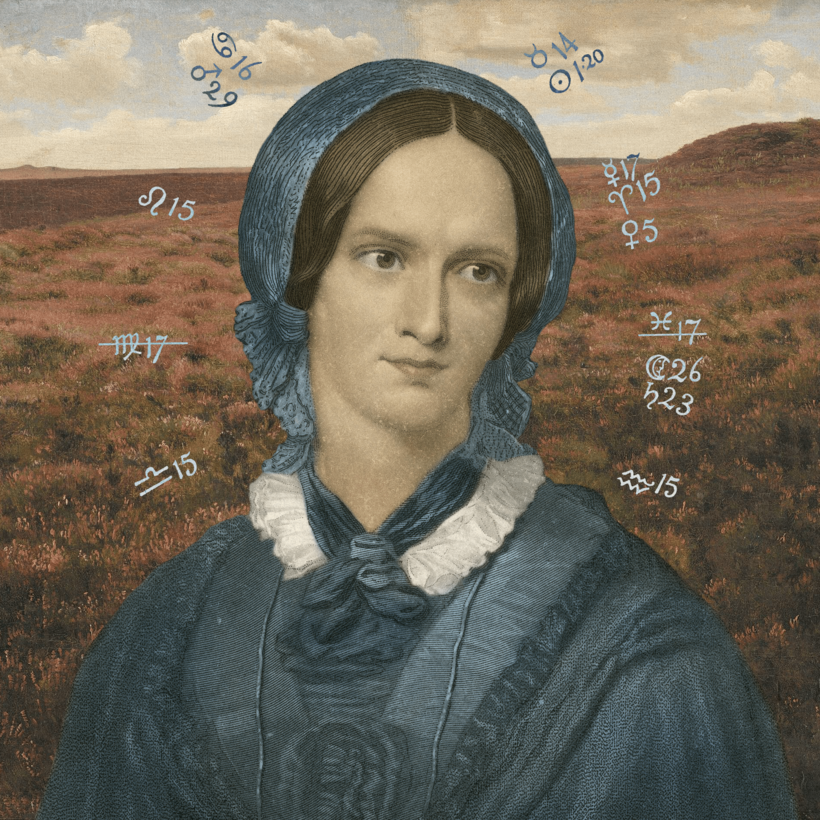

Shortly before she became one of the 19th century’s most scrutinized women, Charlotte Brontë told a friend that if strangers happened to look at her once, they made sure never to make the same mistake again.

She meant it humorously, but the remark also reflects her long experience of feeling underestimated, ignored, or pushed aside. Today, though, she is remembered as confident, erudite, and fiercely ambitious. Legend has given her a stature that life rarely did.