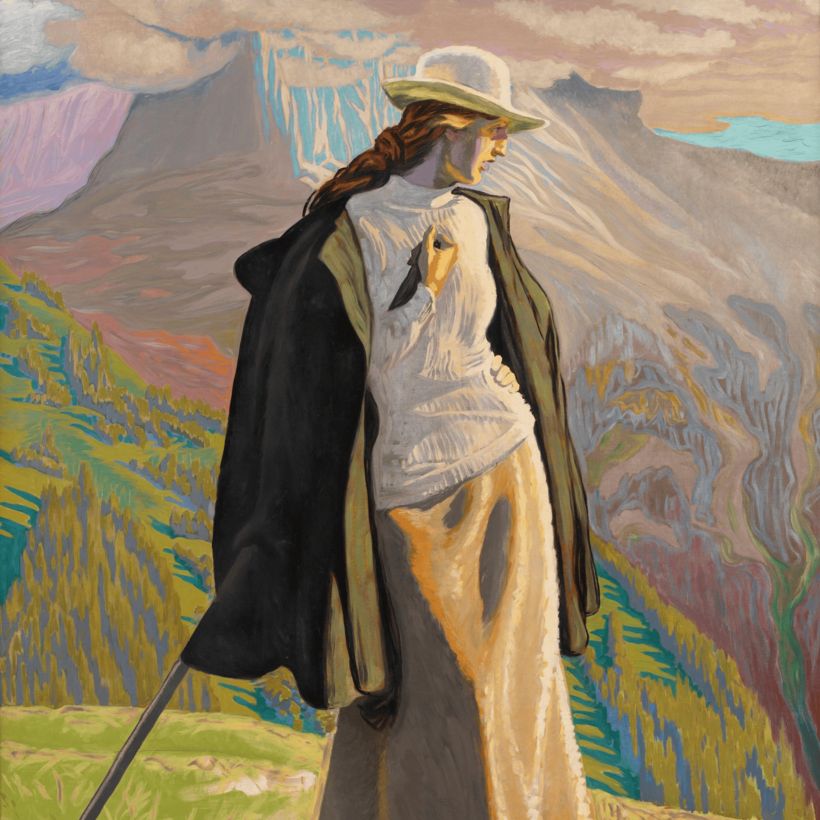

A few years ago, at the National Art Gallery in Copenhagen, I found myself face-to-face with an immense painting called A Mountain Climber. Painted in 1912 by the prominent Danish artist Jens Ferdinand Willumsen, it showed a curvaceous Nordic beauty, elegantly dressed in a long, sweeping skirt, form-fitting sweater, brimmed hat, and fashionable cape, one hand cradling the carved end of a long walking stick as a mountainscape rose behind her. But what was a Danish woman—Willumsen’s second wife, a somewhat Nietzschean air about her—doing among the dramatic peaks of the Alps? Was the skirt really the best option for climbing? Were there more female hikers like her? What drew them to such heights? And is anyone else reminded of when Martha Stewart and some other gals from the society pages tackled Mount Kilimanjaro?

For answers—granted, not about Martha—there’s now Mountaineering Women: Climbing Through History, by Joanna Croston, director of the Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Festival & World Tour. (How’s that for a title?) The introduction is by Nandini Purandare, president of the New Delhi–based Himalayan Club, an organization founded in 1928 under the British Raj.

There appears to be something in the upper reaches of publishing’s air right now. This past April, Melissa Arnot Reid, the first American woman to summit Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen, published the raw confessional Enough: Climbing Toward a True Self on Mount Everest. This month saw the release of Turn to Stone, aspiring rock-climbing star Emily Meg Weinstein’s memoir “of sex, angst and rocks.”

Though less frequently than once upon a time, climbing also brings news of disaster. On July 30, the front page of The New York Times carried the headline “Laura Dahlmeier, Gold Medal–Winning German Biathlete, Dies in Rockfall.” A reminder of mountaineering’s innumerable perils, the apple-cheeked 31-year-old met her tragic end in Pakistan—home to the majestic and difficult Karakoram, which contains the second-highest peak on earth after Everest—the 28,251-foot K2—and extends to the borderlands of India, China, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan, where the political circumstances are at least as tricky as the terrain.

Complicated politics are one unifying element among Croston’s climbers, as they scatter across the globe from diverse countries of origin while history unfolds. Raised in postwar Communist Poland, Wanda Rutkiewicz, who broke records summiting K2 and Everest, spoke volumes when she said, “I’d rather not waste my life, I prefer to risk it.” The petite Bangladeshi climber Wasfia Nazreen refused to conform to the strictures of her Muslim upbringing, throwing herself into the Free Tibet movement until the Dalai Lama encouraged her to focus on the rights of young women in Bangladesh. In 2011, the 40th anniversary of Bangladesh’s independence, she announced a plan to climb the highest peak on each continent, known as the Seven Summits. By the time she summited the Carstensz Pyramid in Indonesia, in 2015, she was a national hero.

As far back as 1808, the Swiss tea-shop owner Marie Paradis defied naysayers to prove that a woman could scale Western Europe’s highest peak, Mont Blanc. The Alps, the darlings of the Romantic era, also provided a naming opportunity for the Ladies’ Alpine Club, the first all-female mountaineering group, formed in London in 1908 to combat the otherwise prevalent isolation among women—certainly not “ladies,” their detractors sniffed—who liked to climb.

An assiduous compendium, Mountaineering Women has in its taller-than-wide shape numerous graphs, charts, scientific illustrations, glossaries, and statistics, intimations of a very wonky logbook. But its main resolve is to scoop up women mountain climbers—whether on rock, moraine, ice, or combinations thereof—who have long been pushed to the margins of a sport and a history “almost completely dominated by men,” and deposit them at the center of the action.

Each story comes with specially commissioned ink illustrations in firmament-colored blues, some with numerically dotted lines that trace significant trails blazed, as well as photographs that lean into the black-and-white language of documentary reportage. Three sections of breath-gulpingly striking full-color photographs, arranged for maximum effect, zhoosh up the text to convey the achievements of Croston’s 20 crème de la K2-climbing crème, and give lie to the mountaineering world’s doubt-sowing discrimination and misogyny. This is not a book that obliges Donald Trump by referring to Alaska’s Denali as Mount McKinley.

Somewhat less enlightened is the book’s uncritical perspective toward those who trade in woo-wooisms, such as “the deities that live among the Himalayan peaks,” though there’s more sense to mountains as incarnations of the eternal female—Mount Everest’s wayback name, for instance, is Chomolungma, or “Goddess Mother of the World” and has some historical precedent, as both the Berbers of Morocco’s Atlas Mountains and the Incas of the Andes were anciently animistic civilizations where women stood among the clouds.

But so much of modern climbing for women really did start with women in skirts. More than once Henry James’s Mary Garland, the grounded American uncowed by the Alps in his early novel Roderick Hudson, came back to me as I read Croston’s book. In 1838, the monied Frenchwoman Mademoiselle Henriette d’Angeville, pictured in a lithograph with her heavy coat cinched ladylike at the waist, faced off against Mont Blanc. In her formidable amount of luggage, in addition to a cask of vin ordinaire for her porters, a feather boa was packed.

With mountaineering garb and equipment now streamlined and safety-proofed with high-tech fabrics, lightweight alloys, and computer-generated design, with altimeters and helicopters primed for rescues, and with corporate sponsorships and media deals in the can, it can seem hard to draw a through line from such pioneers. But however deadly the outcome for some, Mountaineering Women manages: from hand-jamming to pendulum swings, Croston’s climbers climb because they wouldn’t know how not to.

Celia McGee, a New York–based arts-and-culture reporter, writes regularly about books for AIR MAIL and The New York Times