When I started writing I Am a Part of Infinity: The Spiritual Journey of Albert Einstein, my plan was to trace how Eastern religious and philosophical traditions had shaped Albert Einstein’s spirituality. I’d been deeply immersed in Eastern spirituality all my adult life, and just by looking at some of Einstein’s quotes, it was obvious that the East had influenced his thinking. As I began conducting research for the book, I discovered plenty of direct evidence for this.

Einstein had admired Mahatma Gandhi above any other living human being and studied his writings in detail. He’d also met repeatedly with the Nobel Prize–winning mystical poet Rabindranath Tagore, who told Einstein about the nondualistic pantheism of the Upanishads, some of the oldest and most sacred scriptures of India. And Einstein owned not one but five different editions of the ancient Chinese Taoist text Tao Te Ching—one of which he highlighted more heavily than any other book in his large personal library, which totaled some 2,400 volumes.

All of this was intriguing but not especially surprising. What did come as a total surprise was the discovery that a different spiritual tradition, one born in the Western world, had in fact exerted an enormous influence not just on Einstein but on almost every other major physicist of the last 500 years, including Johannes Kepler, Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo, and Isaac Newton, as well as key founders of quantum mechanics such as Wolfgang Pauli and Werner Heisenberg. And this little-known spiritual school also had an immense impact on the Western philosophers Einstein most admired, namely Baruch Spinoza and Giordano Bruno.

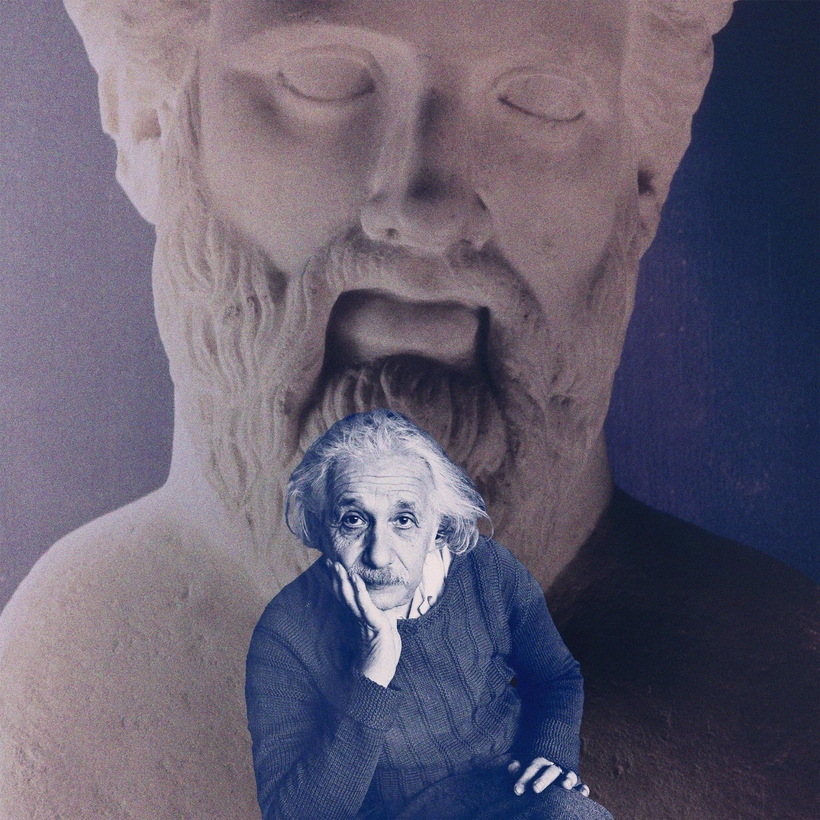

The tradition in question was known as Pythagoreanism. Founded by a Greek sage and mathematician known as Pythagoras, who lived from around 570 to 495 B.C.E., the philosophy embraced a strange mix of science and spirituality, mysticism and mathematics. The fundamental Pythagorean creed was that the cosmos was an integrated entity organized according to a divine and rational order—and that the human mind could grasp this underlying order through mathematics. It was the closest anyone had come to a kind of scientific spirituality, and these ideas ended up shaping all of modern science, especially physics. In fact, ever since the start of the Scientific Revolution, in the 16th century, the Pythagorean worldview has been the major inspirational force for all of the great thinkers who tried to understand the ultimate nature of reality with mathematical constructs.

Einstein was well aware he was carrying on this ancient tradition in his own work. He saw himself as a member of a timeless fellowship of spiritual-scientific seekers who were following in the footsteps of Pythagoras—thinkers and philosophers who sought to know the divine through the highest exertion of the human mind. The results: a total revolution in our view of the cosmos and its basic building blocks over the past five centuries speak for themselves.

I was astonished to discover just how oblivious I was to the deep spiritual roots of modern science—and to the secret spiritual yearnings that drove our greatest scientists to make their most important discoveries. Learning just how many of the major physicists of the modern age have been enchanted with the Pythagoreans makes it easy to understand how Einstein, who described himself as agnostic, could have held such a strong conviction that our cosmos can be understood through a mixture of religion and science. And his striking example shows us that we still have much to learn from the little-known spiritual traditions that lie at the origin of the Western world.

Kieran Fox is a neuroscientist, doctor, and psychiatry-research resident at the University of California, San Francisco