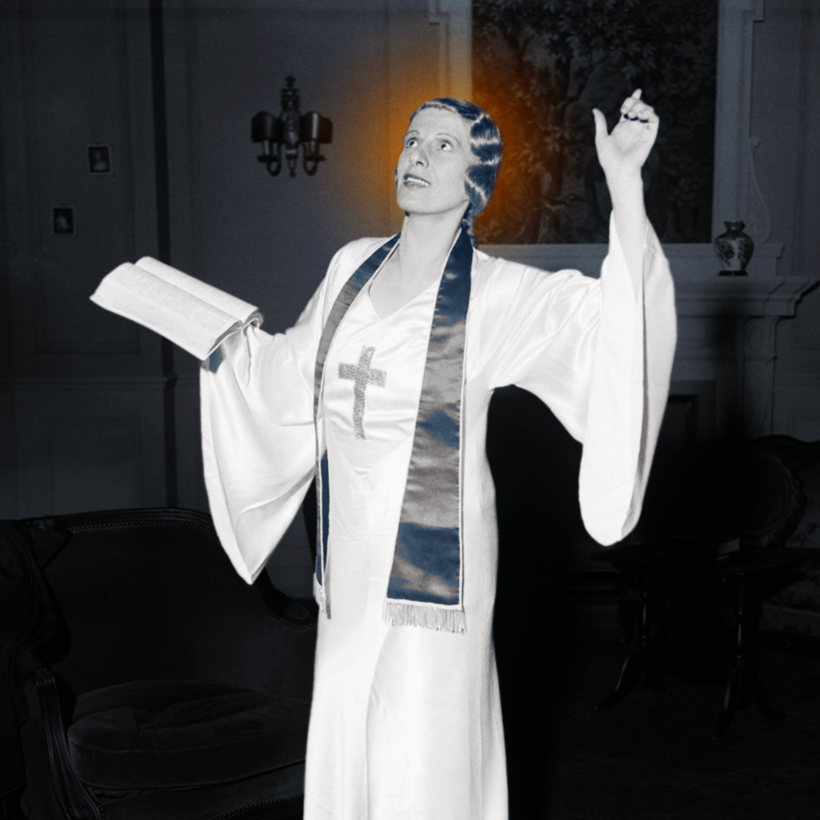

I first heard about Aimee Semple McPherson at the University of Chicago Divinity School, where I was earning a master’s degree in religious studies. McPherson, or “Sister Aimee” as she was sometimes known, was an early popularizer of Pentecostalism, a modern Christian movement that emphasizes a direct connection to the Holy Spirit. Just a few years after finishing my degree, on my way to work at the Los Angeles Times, I would drive by Angelus Temple, the giant white megachurch in Echo Park founded by McPherson in 1923. A female powerhouse in American religion who had been forgotten—that figures, I thought.

Then I read that McPherson had disappeared while swimming in the Pacific Ocean in May of 1926. She was taken for dead and mourned by the national media, only to miraculously walk out from the deserts of Mexico 36 days later, more than 600 miles from where she had gone missing. Unscathed, she told a bizarre story of being kidnapped. But soon, when no sign of the kidnappers materialized, law enforcement began to doubt her version of events. That year, the legal proceedings surrounding her alleged kidnapping became the most expensive in Los Angeles history—until the Manson murders, almost 50 years later.

I was fascinated by McPherson’s mix of historic importance and the fantastical nature of her scandal. My plan for writing Sister, Sinner: The Miraculous Life and Mysterious Disappearance of Aimee Semple McPherson was to trace her rise from farmland obscurity in Ontario, Canada, to being one of the most well-known women in the world by the 1920s. It would be a Wolf of Wall Street–style story—but centered around a female religious leader. I considered ending the book in 1927 with a surprise twist that McPherson allegedly blackmailed William Randolph Hearst into paying off a key witness in her kidnapping trial. But a year into research, with access to hundreds of pages of court records and thousands of newspaper clippings, I discovered something shocking: McPherson spent the last seven years of her life under a conservatorship. She was the Britney Spears of the 1930s.

I assumed, as many readers likely will, that conservatorships were a relatively new phenomenon—something that only came into public consciousness with Spears and, more recently, Amanda Bynes and Wendy Williams. It’s disturbing to follow these stories of women who seem to collapse under the pressure of fame—and yet are still expected to generate value. When Spears and Bynes were placed under conservatorships, we were told they were incapable of managing their own lives. A conservatorship is meant to protect the vulnerable, but it can look more like a legal leash: a declaration that these women are unfit for autonomy but fit to turn a profit.

Nineteen twenty-seven should have been McPherson’s comeback year. She had beaten the charges of faking her own kidnapping and was more notorious than ever. But instead of a victory lap, it was the beginning of her own unraveling. After bitter fights over the financial management of the church, McPherson’s mother stepped away from helping run her daughter’s empire. The Great Depression loomed. Life at Angelus Temple came to mean lawsuits, betrayal, mutiny, power struggles, and an ever growing payroll.

One by one, those she relied on turned against her, collectively filing dozens of lawsuits that drained her resources and resolve. Investors in her real-estate schemes sued for fraud. Her business manager, press agent, real-estate partners—all sued.

According to her family, McPherson was simply a fool when it came to money. All the qualities that made her charismatic failed her when it came to finances. “Mother was frankly starry-eyed and visionary,” her daughter, Roberta, later said. But “very gullible. She never doubted anything.”

Throughout the Depression, despite financial and legal struggles, McPherson maintained a busy schedule. By the end of 1934, Angelus Temple boasted she had preached to more than two million people that year. But soon after, McPherson retreated from the world. In a deposition for one of the numerous lawsuits, Rheba Crawford—an assistant pastor at Angelus Temple and, later, a rival—described her as afraid and defeated. “She is the most tragic figure in America, living in mortal fear that the glories of her past will be taken away from her.”

By 1937, at 47, McPherson saw her life unraveling. She grew estranged from her daughter, and financial pressures escalated. Her accountant, Giles Knight, was given control of her life. Described by staff and parishioners as stern and paternalistic, he effectively placed her under house arrest. Her estate was sold, and he moved her into a modest home in Silver Lake, next door to his own. She was not allowed to see anyone without his approval or to leave the house without permission, except for preaching or teaching at her Echo Park Bible college. Even her mother and daughter were not on the list of approved visitors. Those who broke the rules were subject to Knight’s legendary temper.

Fewer details are known of those years because she dropped out of the news cycle. The media, once obsessed with her, turned away. “The first time it was a sensation. The second it was still good. But now it is like the ninth life of a cat, about worn out,” the Los Angeles Times sneered in 1937, calling for a moratorium on coverage of McPherson.

McPherson spent her professional life sharing the intimate details of her personal life. She spoke openly of breakdowns, heartaches, family drama, and her medical history. But in her final years, she went quiet. It’s a heartbreaking example of how old these patterns are when it comes to women and fame. Even as we celebrate female stars for their influence, charisma, and talent, the conservatorship becomes a disturbing legal expression of a deeper contradiction: we don’t trust these women to make choices for themselves, but we still expect them to perform and entertain us.

Claire Hoffman is a journalist, author, and assistant professor of journalism at the University of California, Riverside