Ambitious young artists know they’re only as good as their first collectors. The right ones send a powerful signal, marking an artist as worth watching and worth buying.

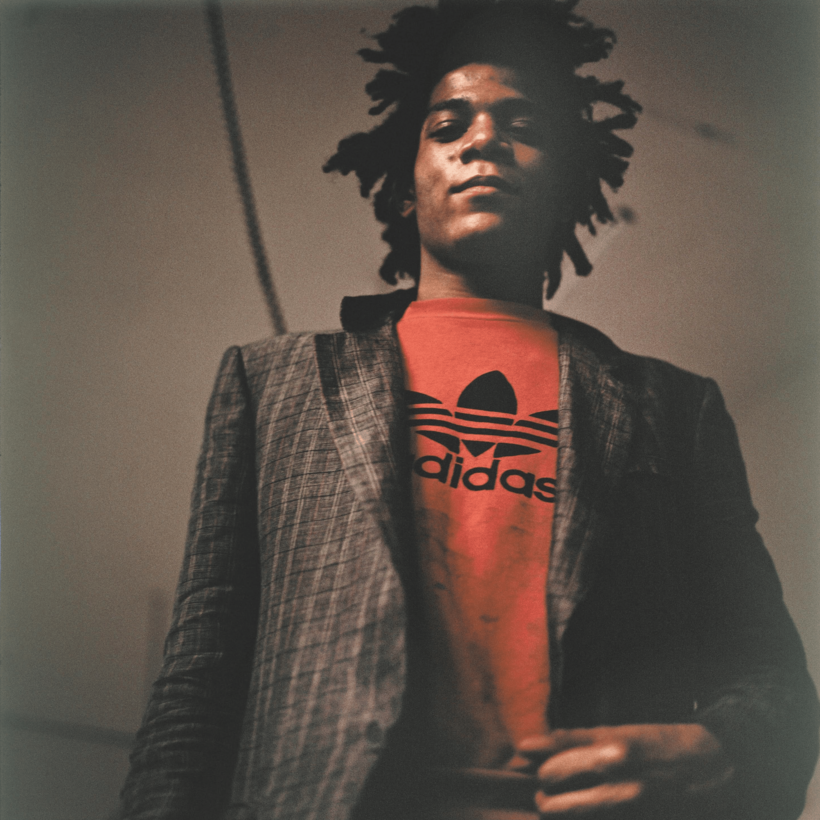

While writing my book Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Making of an Icon, the first major biography of the artist in nearly 30 years, I set out to track down his earliest collectors, the ones who believed in him long before Andy Warhol entered the picture. I knew a few from my time as president of the Americas for Christie’s, but the one that intrigued me most was Stéphane Janssen. His name surfaced repeatedly in catalogues as the owner of key early works, yet he had vanished from view, leaving no digital trace. During the coronavirus lockdown in July 2020, I found one of his sons, who connected me to Janssen himself, then 84 and eager to share how he came to collect Basquiat and know the artist personally.