As an author of World War II nonfiction books, I am continually amazed by how many “untold” stories are still out there about a war that ended 80 years ago. This is especially true given that of the 16 million Americans who served in that war, less than 40,000 (or 0.125 percent) are still living; a number expected to halve by next year.

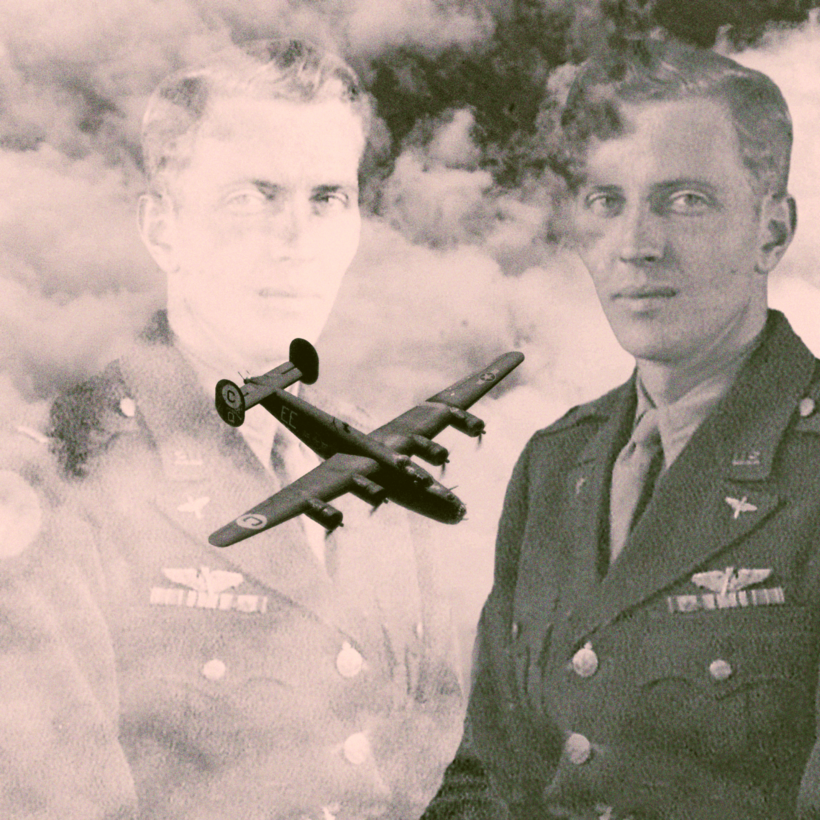

In my new book, Midnight Flyboys, I relay another of those underreported yet incredible stories—this one about a group of U.S. B-24 airmen ordered to “forget everything you saw and did” before going home at war’s end. Many did not tell their families what they did in the war. Not until 50 years later, when the wartime files of the O.S.S.—predecessor to the C.I.A.—were declassified, did the aging veterans feel free to talk about their cloak-and-dagger missions over Nazi-occupied Europe. By then, many of their brethren, still following orders, had gone to their graves, tight-lipped to the end.