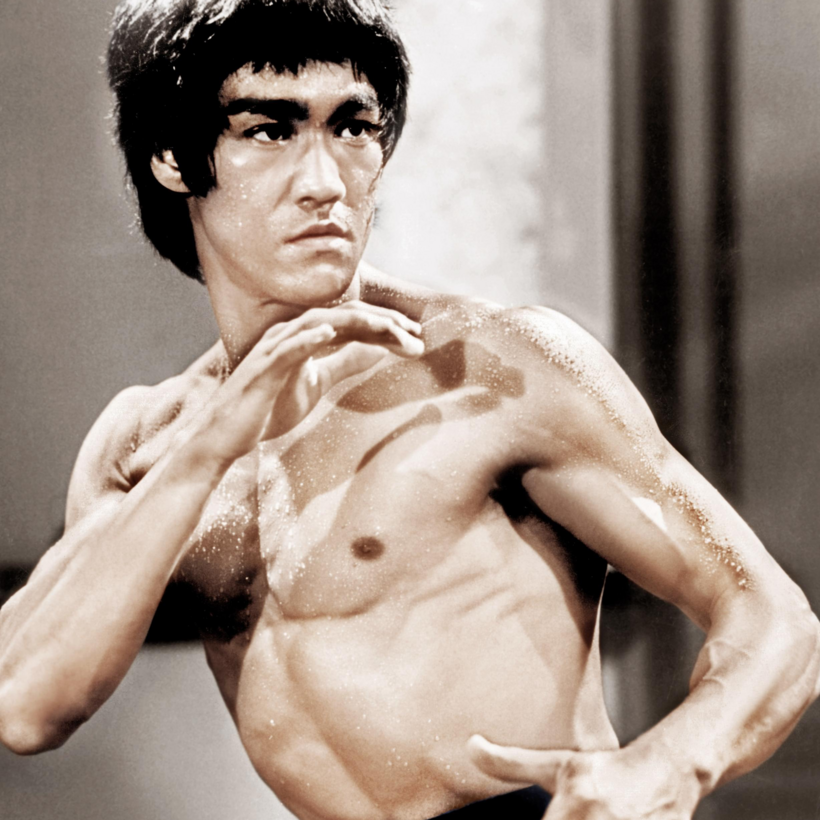

When Bruce Lee hit movie screens in August of 1973 with his instant blockbuster, Enter the Dragon, everything about him seemed counter-intuitive.

Most action heroes at the time—think Clint Eastwood’s “Dirty Harry” Callahan or Roger Moore’s James Bond—operated using guns or gadgets. But Lee shocked audiences because he fought armies of bad guys with his hands, legs, and maybe a stick or two.

He was different from the conquering protagonists of the West. He sweated and bled like the rest of us. When he triumphed, it was a victory for underdogs everywhere. He seemed like Superman and Everyman all at once.

But less than a month before the premiere of Enter the Dragon, Lee suddenly died from cerebral edema, officially ruled by the Hong Kong coroner’s office to be a result of over-the-counter aspirin tablets that he had taken for a headache.

When audiences saw his memorable performance, they could hardly believe a man this focused, determined, and alive could be dead. For a decade, conspiracy theories about his death and a wave of exploitative films featuring Lee look-alikes —dubbed “Bruceploitation”—fed an insatiable demand for his presence.

But he was gone. The man who once appeared so unstoppable had somehow been unimaginably fragile.

Some biographers have depicted Lee as a single-minded man in control of his own destiny. In my research, by contrast, I was continually stunned at how vulnerable Lee felt. His personal papers reveal how self-doubt and dejection followed him throughout his life.

Lee came of age in the chaos of post–Chinese Civil War Hong Kong, where a new generation of young people had formed an underground fight culture. It was in this context that the teenage Lee started learning a form of gōngfú—later Americanized as “kung fu”—called Wing Chun.

He began living a double life. He had become a minor teenage idol through roles in Chinese movies such as Darling Girl (1957), which showcased the dance-floor skills that eventually landed him the title of Hong Kong’s cha-cha champion in 1958. But Lee was also developing a rep on the street, quenching his taste for blood by picking fights with British prep-school students and rival gōngfú practitioners.

His parents, fearing he would get himself killed, put an end to his juvenile delinquency by sending him back to the city of his birth, San Francisco, at the age of 18, with $100 in his pocket.

(Lee was an “anchor baby,” that pejorative referring to the American-born children of migrants in the U.S. on temporary visas. If President Trump’s executive order canceling birthright citizenship was the law of the land when he was born, Lee—like Kamala Harris and Marco Rubio—could have been deported.)

As I was digging through the Bruce Lee archives while doing research for my book Water Mirror Echo: Bruce Lee and the Making of Asian America, I came across a fading writing tablet. On his three-week journey by boat across the Pacific, in the spring of 1959, he had used it to compose letters to send back home and to capture his innermost thoughts. Accustomed to being the center of attraction, Lee was now alone, far away from his family, friends, and streets. His confidence was badly shaken.

Previously a poor student, he began reading intensely—martial-arts texts from China and Britain, unsurprisingly, but also dictionaries of American-English idioms and classics of Chinese philosophy. His notes to himself in the margins, mostly written in Chinese, were unexpectedly sad. He wrote four-character chengyu—Chinese idiomatic expressions—he had memorized. One read, “Trying to be clever, one makes a fool of oneself.” Another: “Forgive others, but not yourself.”

Over the next six years, he lived an unusual life. At 20, just two years after his arrival, he was teaching gōngfú to Black, white, Japanese, and Hispanic Americans. He soon became the face of the Chinese fighting arts in America, a renegade with flying fists and legs. But the schools were difficult to maintain, and he gave up his dream of running gōngfú schools when, unexpectedly, Hollywood came calling.

In 1966, he co-starred in ABC’s prime-time show The Green Hornet as Kato, the chauffeur, cook, and manservant who also saves the day in nearly every episode. But the show ended after one season, and as he realized that Hollywood would never give him the lead roles he thought himself capable of filling, he grew restless and despondent. To the outside world, Lee was a pillar of confidence and ambition. Some considered him annoying or even self-aggrandizing. But his personal notes and writings disclose his deep insecurities.

In his moments of inner turmoil, he turned to American self-help ideology. From Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich, he learned the power of positive thinking: If he just repeatedly reminded himself what he wanted, he could manifest it. He told himself every day he would be a breakthrough Asian star in the United States.

But then he was turned down for the starring role in ABC’s Kung Fu, a series that showcased the martial art that he had done more to popularize than anyone else in the U.S. and for which, as an actor, he was uniquely qualified. The role was given instead to the white actor David Carradine, who played it with taped-back slanted eyes in yellowface. For the next two years, Lee concentrated on becoming the biggest star in Asia, and he succeeded as the biggest box-office star of all time.

By the end of 1972, he began focusing on his return to Hollywood, where he hoped to leverage his stardom in Asia in order to improve the image of Asians and Asian-Americans. He thought he had the perfect vehicle in a movie he wanted to call Enter the Dragon. He had written scenes for the film that demonstrated the wisdom of Zen and Taoist thought. But his own producers refused them, so he staged a one-man boycott, refusing to come to the set until they finally caved. Those scenes—which include an exchange between Lee’s character and his Shaolin sifu (teacher) as well as a teaching session with a young student—lend the movie some of its enduring soul.

Lee had one last fight with the studio when they revealed they wanted to change the title of the movie to Han’s Island, after the Chinese villain’s lair. The studio heads, Lee feared, were more comfortable with a title that perpetuated the stereotype of Asians as evil enemies than with one that suggested the arrival of a new kind of hero. Lee hinted that he was ready to walk if the title was changed. As it became clear to the studio executives just how big the movie could be, they finally relented.

But all these off-screen fights had taken their toll. Enter the Dragon ends with a premonitory scene that exposes the actor’s real-life exhaustion. Lee would not live to see his greatest success.

It would take another generation for his son, Brandon Lee, to break through as the Asian-American star of The Crow (1994), only to be tragically killed on set by a faulty blank. It has taken yet another generation for us to see Asian-American-led films like Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) and Crazy Rich Asians (2018), which demonstrate the breadth of the Asian-American experience.

More than half a century after his death, that is the legacy of an action hero whose greatest fight may have been with his own doubt and despair, and whose victory paved the way for Asian-Americans to be seen in a broader light.

Jeff Chang is a Bay Area–based historian, journalist, and music critic