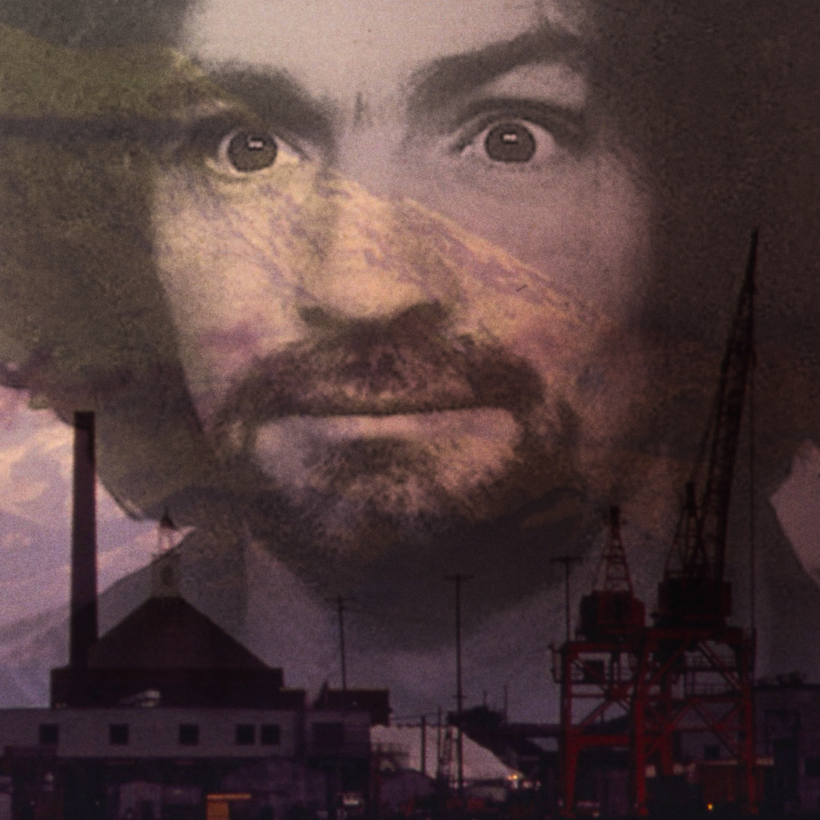

Early in her new book, Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers, Caroline Fraser writes, “It’s August of 1961. I’m seven months old. There are three males who live in what you might call the neighborhood, within a circle whose center is Tacoma. Their names are Charles Manson, Ted Bundy, and Gary Ridgway.” In the margin, I wrote down, “Something in the water?” I had meant it as a joke, but as I read on, I was horrified to be proved right.

In Prairie Fires, her 2017 biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, Fraser showed readers what really went on during the 90 event-packed and deprivation-scarred years of her subject’s life. She deserved that Pulitzer Prize. But nothing could have prepared me for Murderland, which I consumed across state lines, in bars, parks, on trains, buses, and one night, in a poor decision, before bed.

The rigor and precision with which Fraser writes about serial killers is appropriately unnerving. In some instances, it brings to mind Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, particularly its unshakable fourth section, “The Part About the Crimes.” The violence and misogyny, page after page, is similarly unrelenting. And, like 2666, Murderland is brave, ambitious, and tricky.

Murderland is focused on the Pacific Northwest, an area that we culturally associate with Starbucks, Nirvana, Nike, and Microsoft, but which has also produced a staggering number of serial killers. You start to wonder why. But Fraser plays a long game, and before you can begin to figure it out, she weaves in additional narrative threads.

The second strand concerns Fraser’s personal history. She, too, grew up and around the Greater Seattle area. Flashing back and forth through time, she recaptures the feeling of being an awkward and withdrawn child trying to make sense of the world, and eventually charting her own course. In Fraser’s case, that involved freeing herself from both the tyranny of her strict Christian Scientist father and her own desire to kill him. See, violence isn’t just reserved for serial killers, though they always seem to be nearby.

The third strand of Murderland is a reckoning with the violence we have inflicted on the earth over centuries. In it, Fraser does for the Guggenheims, whose art patronage was funded by their mining and smelting businesses, what Patrick Radden Keefe did for the Sacklers in Empire of Pain and Jane Mayer did for the Koch brothers in Dark Money. But this isn’t just a screed against the wealthy. It’s also middle management, the regulators, and the local officials that allow them to continue belching toxins into the surrounding area.

Fraser traces the ill effects of this environmental toxicity and what it does to each of these murderous men who grew up in it, under it, and through it. If it’s in the water, and it is, it’s also in the air, in your clothes, and in your hair. It’s in your skin, it’s in your lungs, it’s in the dirt around you. It’s in the vegetables that grow in the dirt and the animals that provide milk and meat.

Fraser’s treatment of serial killers is the tonal opposite of Ryan Murphy’s. She presents reams of information with very little editorializing or sensationalizing. For Fraser, this book is a map, unifying these three narrative strands and illuminating the ties that bind. Because, “in a chaotic world, maps make sense…. They tell a story. They make connections.”

It’s these connections that make Murderland such a singular reading experience. What happens when the world you live in is literally poisoning you? Can it lead a person to violence, rape, murder, necrophilia? This book is so much more than a compendium of carnage. It’s a warning. We are in trouble. Today, we all live in the United States of Murderland. Sleep well.

Josh Zajdman is a writer, reader, and culture obsessive. On most days, he can be found working on his novel or doomscrolling Instagram