When Pedro Almodóvar was a child in a Catholic boarding school, he was forced to sing for the Salesian monks, who were in charge. He sang so well, in fact, that priests recorded his songs and played them at the church entrance to attract worshippers. “And I remember,” Almodóvar once said in an interview, “we filled the church.”

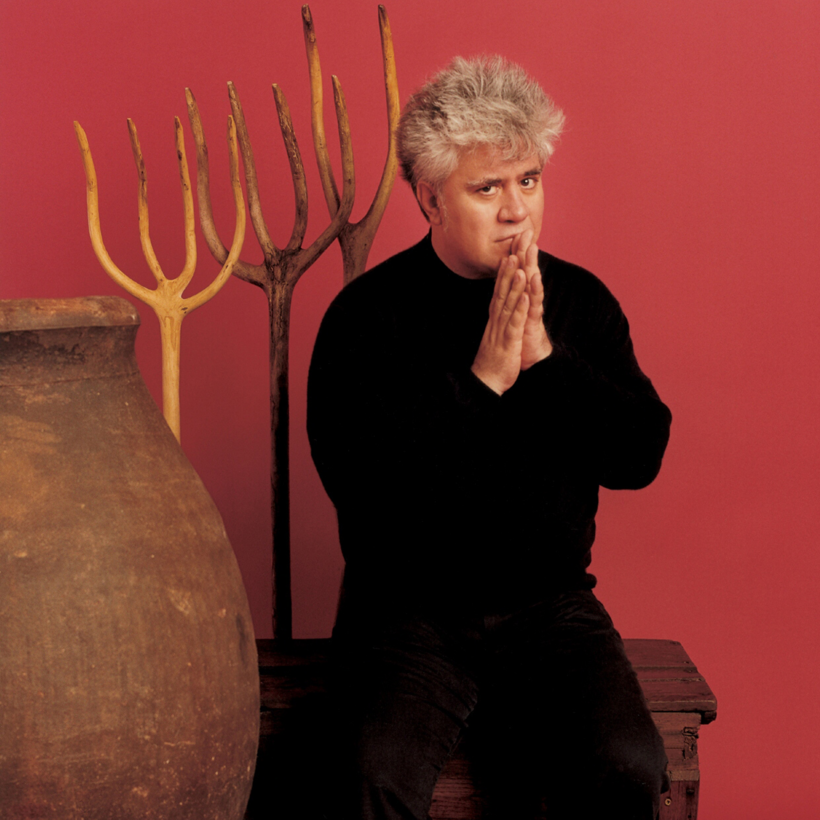

For decades, Almodóvar has filled cinemas with his spectacular, often outrageous films, such as Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988) and All About My Mother (1999). If the image of a student singing for monks sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a scene in Almodóvar’s Bad Education, his 2004 film partly inspired by his abuse during schooling. This kind of reworking of experience lies at the crux of James Miller’s erudite study The Passion of Pedro Almodóvar: A Self-Portrait in Seven Films. Behind so many of the director’s dazzling films and their outlandish-sounding plots, something from the past was burning away in the Spanish auteur’s brain.