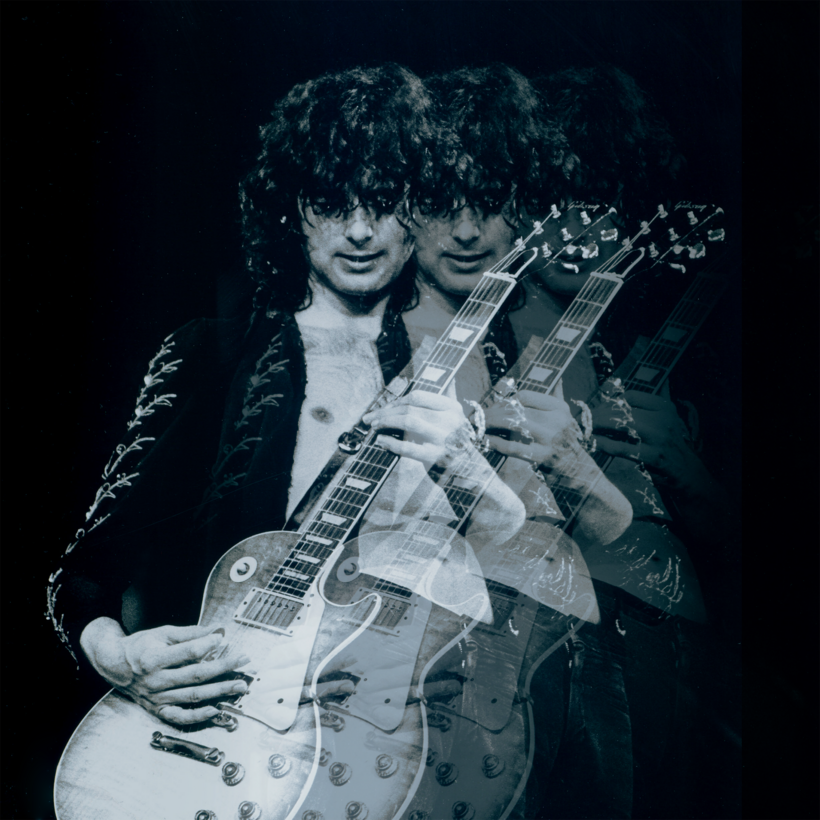

On a snow-blown February afternoon in 1975, a limousine whisked Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page from the band’s hotel near Madison Square Garden, where they’d played a show the night before, down to Manhattan’s then shabby Bowery neighborhood. Arriving at 222 Bowery, Page trudged up the stairs to the fourth-floor loft of the renowned Beat writer William S. Burroughs for an interview about rock ’n’ roll and the exhilaration of wielding sound’s immense power. The conversation, recounted by Burroughs in the rock magazine Crawdaddy, sprawled from the Loch Ness Monster to dolphin communication to, eventually, sound that could kill.

Burroughs’s take on sound’s potential lethality was based on sensationalized media accounts of experiments by the French scientist Vladimir Gavreau, who had tested the effects of high-intensity infrasound (frequencies below what humans can hear) on himself and his colleagues in his lab, on the outskirts of Marseille, a decade earlier. The scientist theorized that just as a sustained high note can shatter a wineglass, sufficiently intense sound tuned to the very low “resonance frequencies” of vital organs might ultimately cause them to vibrate to their breaking point. I read about Gavreau’s work while researching my book Clamor: How Noise Took Over the World—And How We Can Take It Back, specifically for a chapter about the many health dangers of noise beyond hearing loss.