Whatever your opinion of the Microsoft co-founder, it has probably evolved over time. Anupreeta Das tracks the ups and downs of Bill Gates’s career in her eye-opening book, Billionaire, Nerd, Savior, King. Not quite a biography, the author instead uses Gates as a way to examine the hidden influence of billionaires. There’s gossip about Gates’s divorce and disintegrating friendship with Warren Buffett, but Das, a finance journalist, also explains the structures behind his philanthropic foundations and investment firms. It makes for compelling reading.

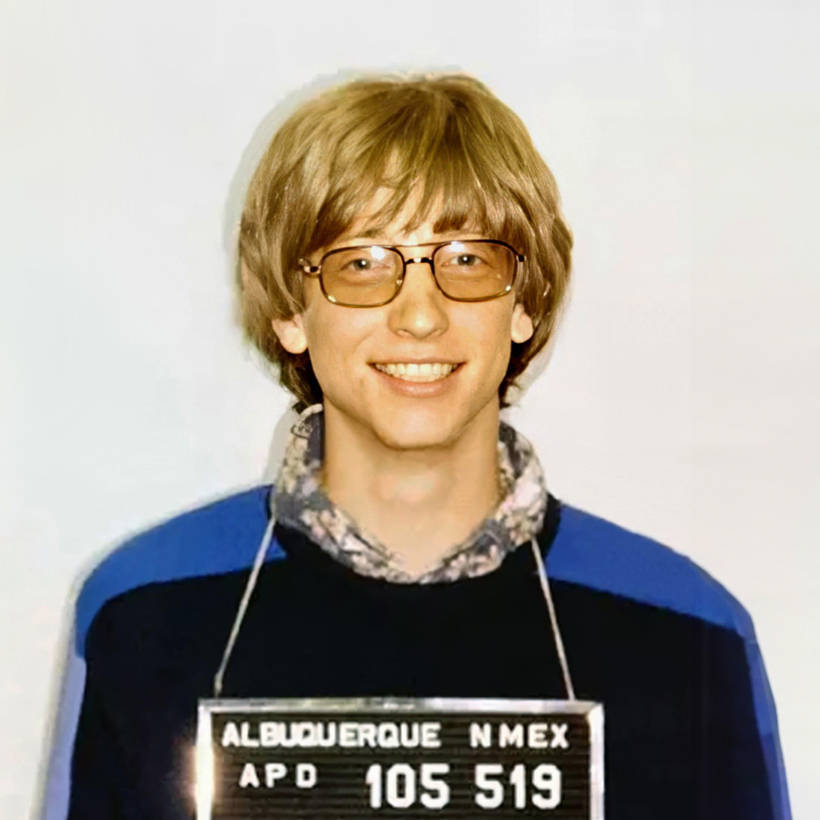

Das chronicles his early success. Gates dropped out of Harvard in 1975 to co-found “Micro-Soft” as a teenager, frantically coding through the night after promising a company software that he hadn’t yet written. The company went public 11 years later, and a year after that Gates became a billionaire — at 31, the youngest in the US and the first from tech. He is now worth more than $154 billion, making him the fifth richest person in the world.