All parents traumatise their children in one way or another. Spare a thought, though, for Moon Unit Zappa. She had to tiptoe around her quiet-please, musical-genius-at-work father, Frank Zappa. She also had to placate her permanently furious mother, Gail, and deal with the obvious social challenge of being called Moon Unit. But worse was to come in her childhood: fame, of sorts.

At 13 she found a way to amuse her parents by imitating the drawling speech of the popular girls at her school in the San Fernando Valley, Los Angeles in the early 1980s. One bubbly extrovert in a white miniskirt fascinated her in particular, gushing such expressions as “Barf me out” and “Gag me with a spoon.” Moon Unit’s father then made a recording of her stream-of-consciousness Valley Girl speak and put it to music. Then things went, like, grody to the max.

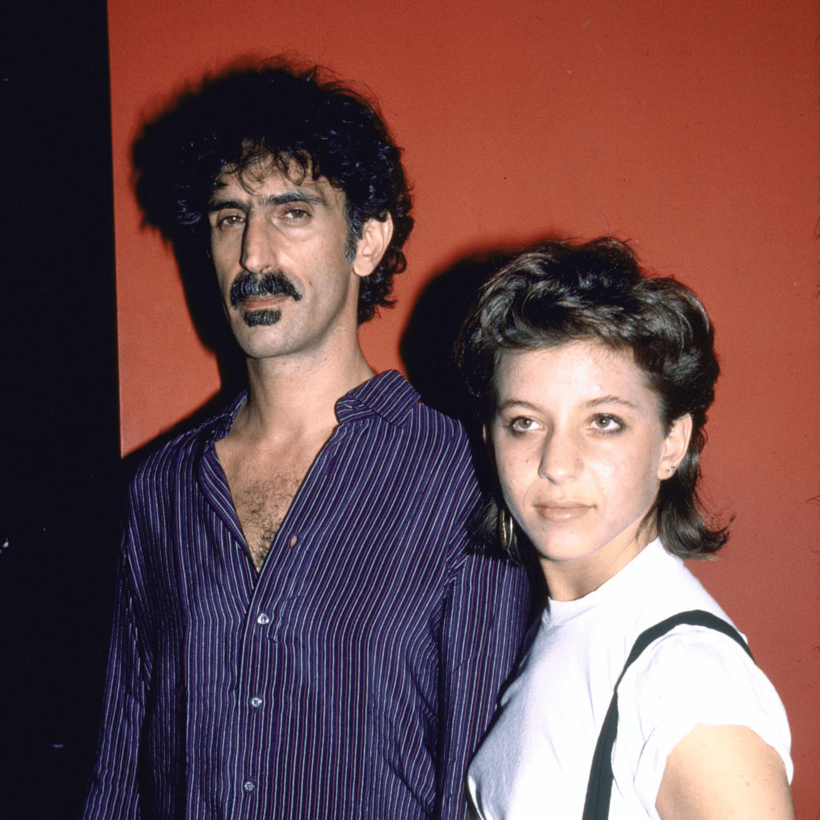

At first the success of the song “Valley Girl” in 1982 put Moon Unit on the radar. Boys in their parents’ cars gave her the hang-loose hand gesture as it played on the radio on the way to school. The very girls dressed in the Flashdance-style, off-the-shoulder jumpers that she mocked in the song offered her newfound respect — “Your dad has a lot of albums so you must have a lot of money!” — on discovering that her father was a famous rock star. Frank Zappa — who combined classical sophistication with jazz-fusion complexity and surrealistic absurdity on cult hits such as “Peaches en Regalia,” “Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow” and “Bobby Brown (Goes Down)” — wasn’t exactly mainstream in the Valley.

But as “Valley Girl” became a global phenomenon, this painfully awkward, acne-ridden 14-year-old was put on the promo circuit and asked endlessly about her “kooky” family. Only Andy Warhol, of all people, was disdainful of Zappa’s treatment of his daughter, criticizing Frank for viewing Moon Unit as his invention, a tool at his disposal.

“No one checks to see if I am OK with this,” Moon Unit writes. “I do not like having strangers’ attention on me. I do not want a spotlight.” But with Zappa going independent and the mercenary Gail as his manager, Moon Unit was now part of the family business and an important cash cow. Will she get the love and respect she has been craving from her parents all these years? No, she will not.

Only Andy Warhol, of all people, was disdainful of Frank Zappa’s treatment of his daughter, criticizing him for viewing Moon Unit as his invention, a tool at his disposal.

Gail, a former groupie who was forever fighting off the other groupies that Zappa was still sleeping with, resented her daughter receiving all the attention. “I am the only reason your father gave you credit on the album and the only reason you are getting any money,” she snarled after “Valley Girl” became a hit, claiming that Frank didn’t want to give Moon Unit a performing or songwriting credit at all.

“I try to hold the paradox of being told at home that my contribution means nothing at all, while the world sees me as clever and funny and talented,” she states, adding: “This will take many steady years of therapy to untangle.”

That isn’t all that needs untangling, judging by this memoir in which Moon Unit articulates the fallout of growing up with parents who think they alone have got it right, who mistake extreme selfishness for enlightenment. This kind of thinking was common in 1970s California but the Zappas went further than most: Gail would announce to anyone who listened that pushing Moon Unit’s younger brother Dweezil out gave her the best orgasm of her life; they had a painting of an orgy in the living room; and she allowed one of Frank’s lovers to live with them. It might make sense if the Zappas had been happy, but from their eldest daughter’s account this hyper-liberal stance seemed as much of a façade as the suburban conservatism they had worked so hard and so publicly to get away from.

Gail’s liberated approach to conflict resolution involved handcuffing a bickering Moon Unit and Dweezil’s ankles together and locking them in a bathroom with a tape recorder, so they could hear “how annoying we were”. Frank, for all of his revolutionary ideas and musical and intellectual brilliance, proved to be an old-fashioned sexist: “Women are f*** toys wrapped in lies about female empowerment”, was his outlook.

Moon Unit saw through her parents somewhere in her mid-teens, once the disillusionment brought by the success of “Valley Girl” had sunk in. “Gail adopts a stance of phoney enlightenment and Zen acceptance to visitors, but inside she is actively vindictive, putting witchy curses in contracts and on women Dad cheats with.”

“I try to hold the paradox of being told at home that my contribution means nothing at all, while the world sees me as clever and funny and talented.”

Adult life for Moon Unit involved the traditional nepo baby journey: ashrams, gurus, unsuitable boyfriends, acting roles, therapy. And while Frank Zappa, only 52 when he died of cancer in 1993, comes across as lovable, if self-absorbed and depressive, Gail’s spitefulness knew no bounds. Moon Unit remembers how, after Frank’s death, “Gail put black fabric over all the mirrors in the house, sold my father’s catalogue and went shopping”. Gail then decided on what should be Moon Unit’s portion of his estate: a piano — which was an instrument she couldn’t play and had nowhere to keep.

In 2002, after plans were made for Moon Unit’s wedding to take place at Gail’s brand-new Malibu mansion, her mother changed her mind at the last minute, screaming: “Why would you make me have strangers in my yard?” Gail even found a way to punish Moon Unit and Dweezil from beyond the grave: by leaving almost everything to their two younger siblings.

Much of this is a familiar, Mommie Dearest-style tale of childhood horror at the hands of Hollywood parents, written in the present historic tense and reaching towards an inevitable form of self-realization. But it is lifted up because Moon Unit is, beyond the therapy-speak, very funny. “Growing up, I was just like you,” she tells us.

“I had a rock star for a dad, two invisible camels for playmates and daydreamed about my future following in Frank’s footsteps by helping people and making them laugh, only I’d be dressed like a nun.” And explaining from a three-year-old’s perspective how her parents had rejected religion and were now “Pagan absurdists”. She surmises: “I think this means they make up their own rules about what to believe on any given day, but also something about oak trees and druids.”

The lesson of the book is a simple one: don’t become famous and have children.

Will Hodgkinson is the chief rock-and-pop critic for The Times of London and contributes to Mojo magazine