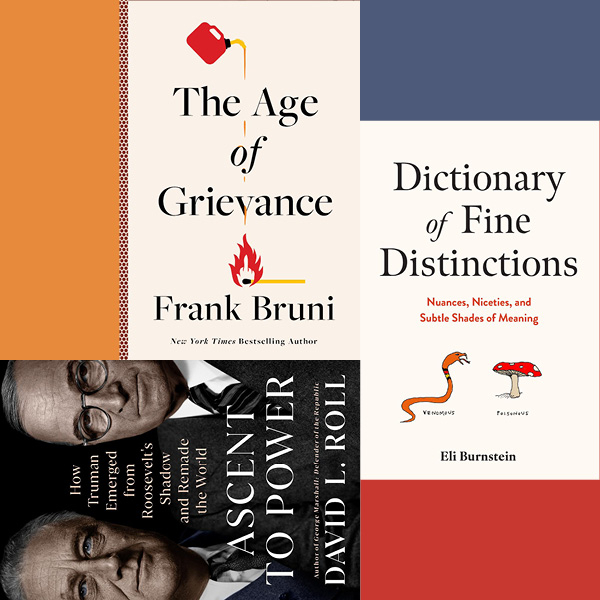

What better guide than Frank Bruni to dissect the age in which we live, an age where folks on the right and left (but primarily on the right) exist in a state of perpetual disgruntlement about how society is stacked against them. Sure, blame Donald Trump for fostering this state of mind, which includes an unhealthy dollop of vengeance, but, as Bruni wisely points out, “we Homo sapiens began pointing fingers and appointing scapegoats shortly after we stood upright, if not sooner.”

Grievance in itself is not bad; after all, the 13 American colonies split from Great Britain out of outrage over punitive taxes. But this time grievance is both more toxic and minute, going far beyond what we once considered to be injustices that needed to be righted. Take Harry and Meghan, who have built a lucrative career from their Montecito mansion in which they air all the slights they suffered from the House of Windsor. Conflict and debate are necessary for any society to thrive, but what is also needed, as Jonathan Rauch calls it, is a sense of “fallibilism,” meaning the intellectual humility that acknowledges we may be wrong and the need to be open to opposite views. Thanks to Bruni’s gifts as a storyteller and stylist, The Age of Grievance is a sharp and witty argument in favor of less righteousness and more uncertainty.

What fun it must be to share a meal with Eli Burnstein, a humorist who has written a highly amusing Baedeker to the words and notions that “we tend to collapse, conflate or confuse.” The fanciful line drawings only add to the pleasure of learning the differences between the Deep Web and the Dark Web, stock and broth, maze and labyrinth, patent and trademark, even deadlift and Romanian deadlift. (The latter involves less bending of the knee.) An equally apt title for this book would have been “Dictionary of Fun Distinctions.”

It is hard to think of another vice president of the United States who was less prepared to assume the highest office in the land than Harry S. Truman, who succeeded F.D.R. during wartime and after only 82 days serving as V.P. He had been kept in the dark about everything, including the development of the atomic bomb. David L. Roll’s masterful study, filled with fascinating details, explains how this once failed haberdasher managed to become such a consequential president and shape the postwar world in ways that still reverberate today. Ascent to Power is narrative history at its best: enthralling, empathetic, and judicious.