In 1848 Europeans revolted from Norway to Sicily and from Switzerland to Portugal. “This was the only truly European revolution that there has ever been,” Christopher Clark writes. “All were included in the band of brotherhood,” the Italian insurgent Enrico Dandolo wrote. “Scarcely a being … could resist the influence of such universal joy and affection.” As Wordsworth might have said, bliss was it to be alive in 1848.

People, it seems, are happiest when in revolt. They’re also angriest, though that comes later. The cacophony of emotions was irresistibly attractive and remains so in retrospect. Life was lived on edge; politics inspired passionate imagination; dreams briefly seemed realizable. “Everything and everyone was in motion,” Clark writes of that exhilarating year. He describes, but also feels, “moments of dazzlement”.

Clark, regius professor of history at the University of Cambridge, didn’t always appreciate the magic of 1848. As a youth he was bothered by its “stigma of failure”. All that febrile energy, all that imagination, produced little of substance — or so it seemed to an idealistic young man. He was also put off by the revolution’s complexity, though that might have been the fault of the books he was forced to read. Historians have a knack for turning 1848 into something stultifying, perhaps by concentrating on politics rather than people.

People, it seems, are happiest when in revolt. They’re also angriest, though that comes later.

This book, in contrast, offers something refreshingly original — it’s fascinating, suspenseful, revelatory, alive. Familiar characters are given vibrancy and previously unknown players emerge from the shadows. Thousands of quickened hearts meld into one revolution, a being of mercurial mood. Clark’s prose is beautiful but also crystal clear; he clarifies as he adorns.

Clark begins with a trigger warning: his first chapter “contains scenes of economic precarity, ambient anxiety, nutritional crisis and ultraviolence”. He then describes, rather graphically, the horrible conditions suffered by Europe’s poor. They lived in dank basements; they were exploited by unscrupulous landlords and bosses; they were ravaged by every passing plague and every cruel authority. This, however, does not explain what happened in 1848. “Social discontent does not ‘cause’ revolutions,” Clark insists. Material distress was, however, “the indispensable backdrop”.

What happened in 1848 was a coming together, a momentary unity of the variously annoyed — liberals, radicals, Marxists, workers. “The revolutions,” Clark argues, “were not the fruit of long-laid plans and conspiracies, but of massive societal protests driven by a combination of political dissent and severe economic dislocation.” The discontented were suffused with an intense love for their country but also with a determination to improve it.

The explanation for why the fire started in 1848, and why it spread so widely, has long baffled historians. Clark, however, is not particularly troubled by this conundrum; he’s more interested in describing the concatenation of events than in discovering its origin. The story he recounts is chaotic, but he’s content with that. This book is long because Clark resists the temptation to simplify.

The discontented were suffused with an intense love for their country but also with a determination to improve it.

This was not an age of reason. Decisions were made on whims, fired by impressions, passions and prejudice. Gossip was the fuel of revolt. In Berlin two hapless soldiers accidentally discharged their rifles. “Neither shot caused an injury, but the crowd, thinking with its ears, was convinced that the troops had begun to shoot civilians.”

In Poland word spread that Austrian authorities were offering bounties for the severed heads of Polish insurgents. “None of this actually happened,” Clark writes, but truth was flexible in those heady days. There were certainly enough verifiable atrocities to convince people of the capricious cruelty of their masters. For instance, Clark relates how a Prussian officer, on finding a suspected insurgent, “pressed the barrel of his rifle onto the temple of a still very young and personable youth and shattered his head”. Even without an Internet word of that outrage traveled at warp speed.

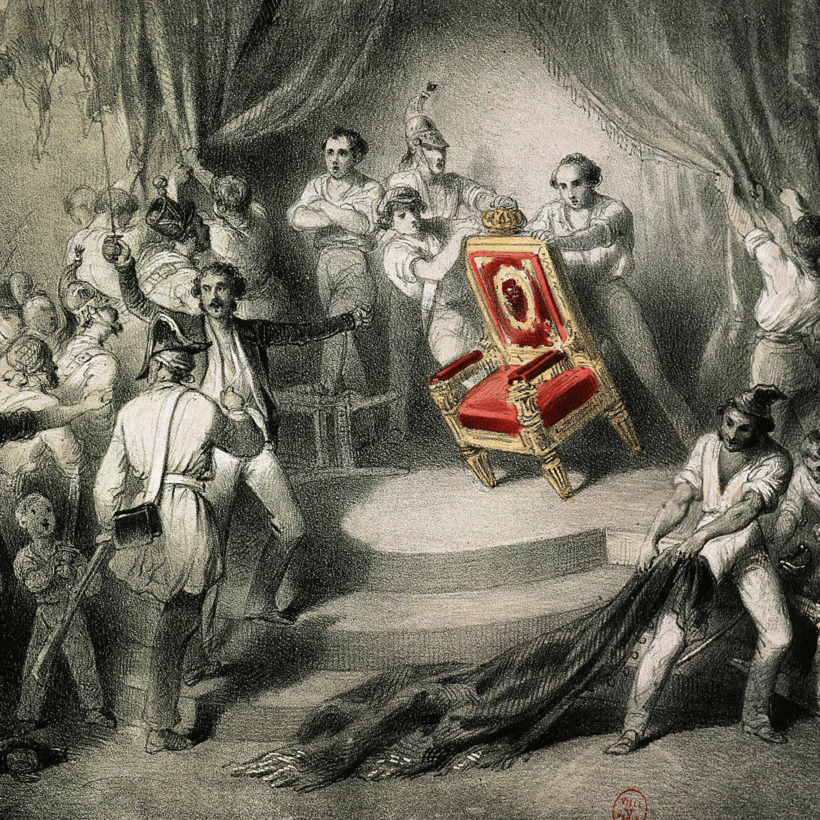

The revolution was briefly a thing of beauty. In Budapest the poet Sandor Petofi quickly wrote the patriotic Nemzeti dal, “National Song”, which was bellowed from the barricades. In cities across Europe revolt took on a theatrical quality. Imagination ran wild. There was a fashion for revolution and a revolutionary fashion. Petofi was “dressed for the occasion in a black silk attila with silver buttons, a raked felt cap with an ostrich feather … tightly tailored trousers and tufted evening shoes”.

Clark crams the events of the early spring, when revolt was fired by hope and love, and when barricades became works of art, into a single chapter that is long but sadly not long enough. I wanted more stories from the streets, but who am I to question this sublime author’s mise en scène? His point here, I suppose, is that hope was fleeting, and that the revolution’s beauty quickly withered like daffodils in April. The rest of the book recounts how fervor was crushed; it is long, detailed and depressing.

The ruling classes, overwhelmed by the force of popular opinion, at first panicked, quickly making concessions. Across Europe the insurgents were invited into various governments and promises were made about expanding the franchise. This was usually enough to quiet the unrest and fracture the fragile unity of the revolutionaries. We sense a formula to neutering revolution: each concession, no matter how flimsy, satisfies a fragment of the discontented, thus decoupling them from the revolutionary whole, systematically eroding its power. Revolutions are killed by hundreds of tiny concessions.

Gossip was the fuel of revolt.

“What was astonishing,” Clark writes, “was the speed and amplitude of the transition from unity to conflict.” Revolution, when played to the tinkling melody of breaking glass, is so much more fun than actually governing. When former insurgents were invited into government they experienced the “difficulty of synchronizing the slow politics of the chamber with the fast politics of the clubs and streets”. As spring turned to summer, love and hope gave way to suspicion and pessimism — in other words, to politics.

Revolution was overwhelmingly masculine, but Clark does not ignore its feminine side. He’s rather smitten by the women who tried to be revolutionaries. They’re fascinating but sadly not very influential. “I regret that I am not a man,” the Croatian schoolteacher Dragojla Jarnevic wrote. She wanted desperately to “join the circles of action in which the whole of Europe is caught up … only I am not allowed”. Illustrations of intelligent politicized women adorn the pages of this book; they share a look of frustration. Clark does not feel the need to honor them by inflating their influence — their enforced enfeeblement makes a better story. It’s brutal but honest.

In midsummer, though passion had given way to politics, the streets remained deadly. Having regained their confidence, rulers everywhere enforced their will with cynical brutality. The violence was no longer beautiful, just bloody. In August Ciceruacchio, one of the founders of the short-lived Roman Republic, and seven others were captured by Austrian soldiers bent on execution. He pleaded that his son of 13 be spared. “We’ll shoot him first,” came the reply. And they did. “Not all deaths were … eloquent,” Clark concludes.

The French novelist George Sand, who earlier in the year had been so hopeful of change, complained about how easily the public will was perverted. Clark tries to find shards of success among the ruins of revolution, but I’m not convinced. Conservatives everywhere skillfully exploited the divisions among the left, as they always do. They coaxed the newly enfranchised “little people” to their side by playing on nationalist themes. In the French election of December 1848 perhaps four million peasants voted for the old guard of Louis-Napoléon, who won 75 percent of the vote. As Pete Townshend once wrote of a different revolution: “Meet the new boss. Same as the old boss.”

Gerard DeGroot is a professor of modern history at the University of St. Andrews and the author of several books, including The Bomb: A Life and The Seventies Unplugged