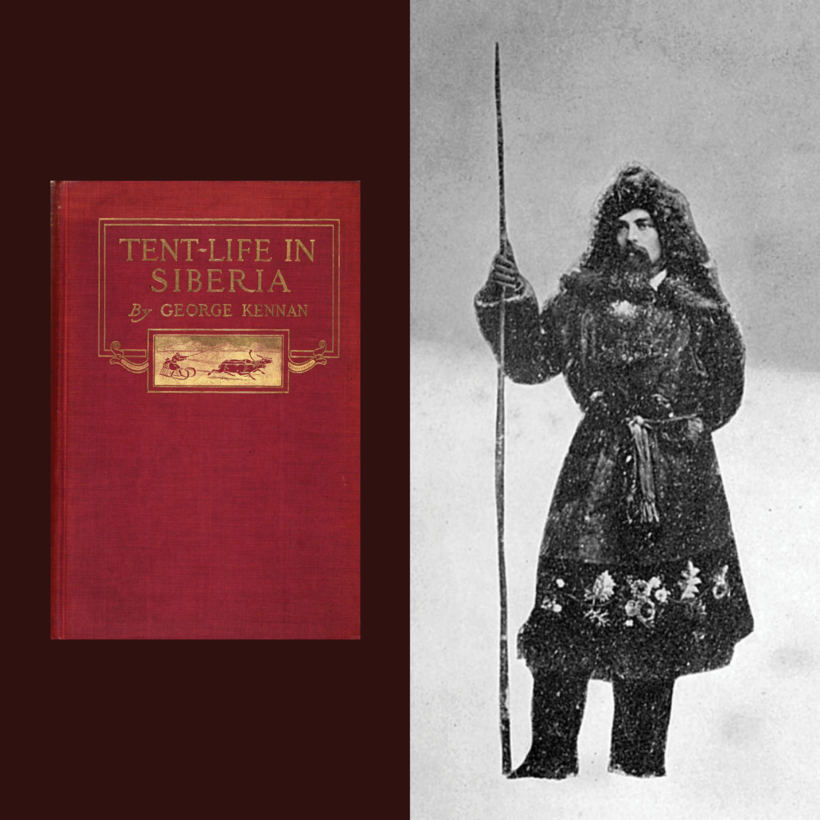

In 1876, Walter P. Phillips, the manager of the Associated Press’s Washington office, offered George Kennan, who was then in his early 30s, the job of covering the U.S. Supreme Court. Kennan had written an acclaimed book, Tent Life in Siberia, about the three years he spent exploring the region’s northeast. But he declined the offer, saying he had no legal experience. “Well, you could not know less than the man currently in that job,” replied Phillips. “And you have the affirmative advantage that you know how to write.” Kennan took the job.

Kennan’s writing talent was an unexpected and delightful discovery when I began researching my book Into Siberia. While his Supreme Court reporting drew praise from every justice, Kennan worked in genres ranging from exploration to investigative journalism to war reporting.