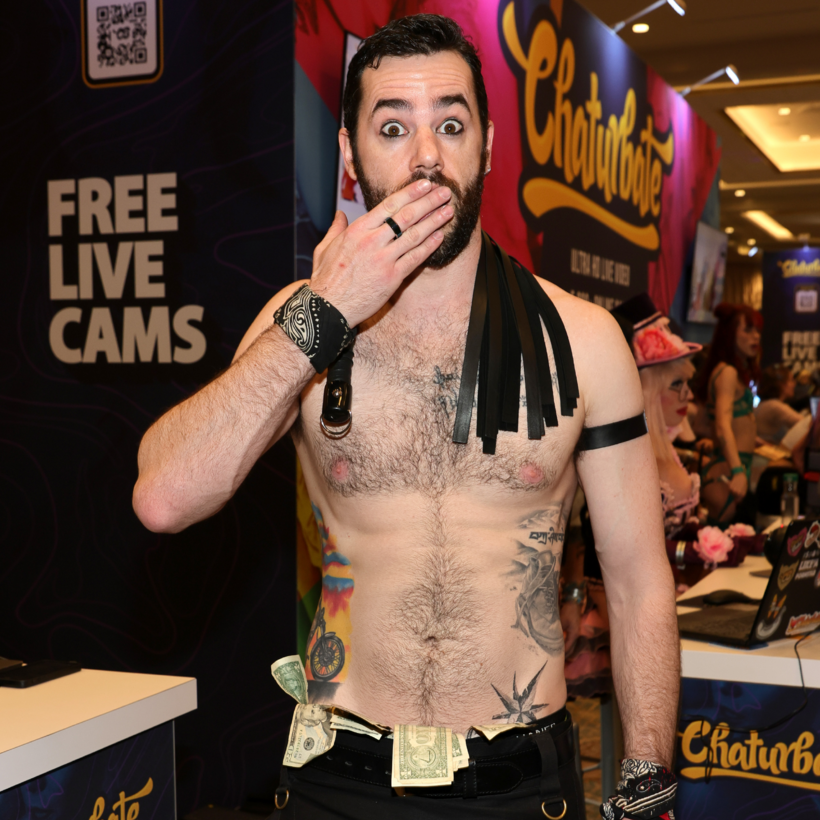

The owners of porn Web sites make more than a billion dollars in annual revenue. Young people growing up in America are almost guaranteed to encounter online porn by the time they are teenagers. Every day, around 130 million people visit the Pornhub Web site, the world’s most popular online porn platform, with the United States generating the most traffic.

Plenty of people—from politicians and activists to sex workers and religious leaders—are outspoken in their beliefs about what we should do about the proliferation of online porn, from how to prohibit young people’s access to removing illegal content and protecting the safety of performers. But as a sociologist, I approach the topic from a different angle.

In my book The Pornography Wars: The Past, Present, and Future of America’s Obscene Obsession, I set out not to convey some ultimate truth about Internet pornography but, rather, to explain how multiple truths come to be told from different vantage points. Just as directors write the scripts of pornographic videos and Web-site engineers craft algorithms to shape which videos users will see, individuals who make claims about the morality of online porn are also crafting narratives that both illuminate and hide certain facts. This, in turn, shapes what we believe about porn.

The danger is that messaging about pornography, which often stems from groups with religious and political ties, gives the illusion that we know the truth about porn—specifically its harms—when we may actually be missing important perspectives.

Consider that 16 states, including Utah (the first) and Arkansas (the most recent), have passed resolutions declaring pornography to be a public-health crisis. The language used in these resolutions, which often draw bipartisan support, makes the problems of porn seem objective and scientific—indicating, for instance, that pornography is biologically addictive. But these resolutions trace back to an advocacy organization led by evangelical Christians who believe that pornography, and all forms of sex work, is morally wrong. These resolutions mask the fact that conclusions about porn’s impact on society are, well, complicated.

Sixteen states, including Utah (the first) and Arkansas (the most recent), have passed resolutions declaring pornography to be a public-health crisis.

Most studies on whether or not pornography is bad for society take place at a single point in time and therefore may find evidence of correlation, but not causation. For example, some studies have found that higher rates of pornography consumption are associated with violent attitudes toward women. A plausible explanation is that violent men are inclined to watch more pornography, not that more pornography causes violence. Similarly, studies have found a negative relationship between watching porn and marital satisfaction for heterosexual men. Is it that porn is bad for marriage, or that people in bad marriages are more inclined to watch porn? We can’t say for sure.

People experience pornography differently based on their sexual identities, experiences, and beliefs about sex. It’s true that watching porn causes problems in the lives of men who view it yet believe that it is morally wrong or addictive. It’s also true that some queer youth find watching pornography to be a source of affirmation and acceptance of their sexuality. It’s true that many porn performers have experienced abuse in the industry. And it’s also true that many sex workers choose Internet pornography as an enjoyable and flexible form of work.

One of the most troubling stories I have heard about the pornography industry came not from the anti-pornography camp but, rather, from a porn-positive performer named Jade. She was subject to horrifying abuse and coercion within the commercial industry. But she insists that the solution for women like her is not necessarily to leave the industry altogether. She argues that the problem isn’t pornography per se, but the abusive men who work in the industry without consequences. Jade remains an Internet sex worker but mostly works independently, producing content for Web sites such as OnlyFans.

What should we make of these seemingly contradictory “truths” told on both sides of the pornography debate? It’s like what Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart famously declared about the definition of pornography: “I know it when I see it.” Pornography depends upon context.

Kelsy Burke’s The Pornography Wars: The Past, Present, and Future of America’s Obscene Obsession is out now from Bloomsbury