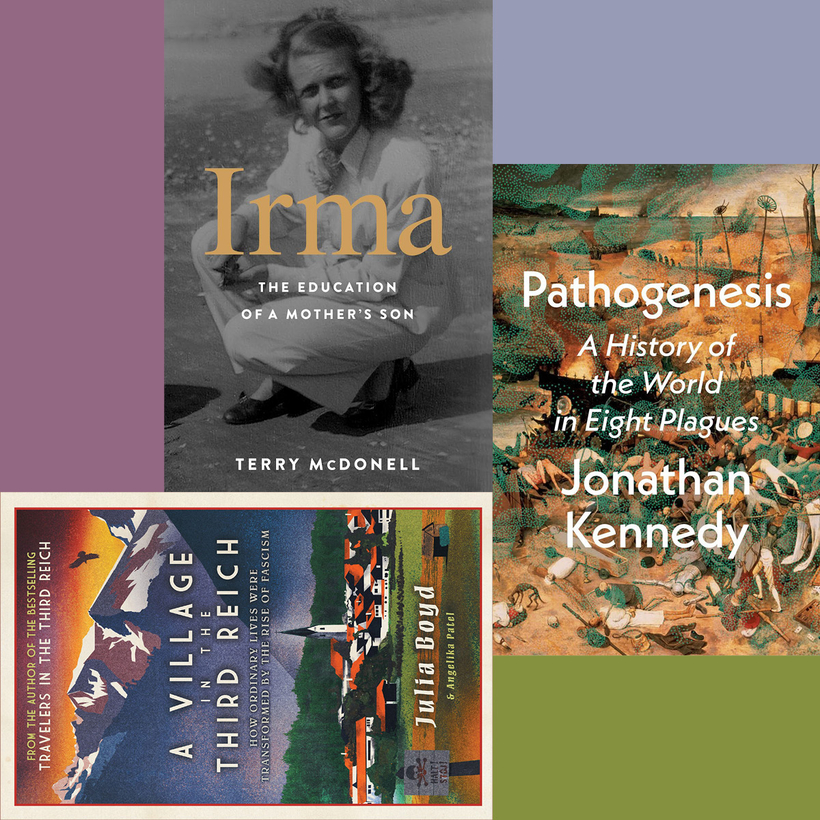

The author has had a storied career as a magazine editor, most notably as editor in chief of Esquire and the managing editor of Sports Illustrated. Those were the glory days of magazines, and Terry McDonell brilliantly captured his professional career and his colleagues in prose (among them George Plimpton and Hunter S. Thompson) in The Accidental Life. He digs much deeper into his life in Irma, the story of his mother and his life with a single mom. (His dad died in a plane crash when McDonell was five months old.) He had a stepfather from hell, a romantic life out of Henry Miller, and an infatuation with the writing style, if not the lifestyle, of Ernest Hemingway. McDonell is a poet at heart (in fact, he has published a wonderful collection called Wyoming: The Lost Poems), and I can think of no higher compliment than to say Irma deserves its place on the bookshelf next to This Boy’s Life, by Tobias Wolff, a superb memoir with the best dedication ever: “My first stepfather used to say that what I didn’t know would fill a book. Well, here it is.”

Some feel history is made by great men, others feel it is made by the common man, but Jonathan Kennedy argues persuasively that history, ultimately, is made by germs. In this wonderfully written survey of eight major outbreaks of infectious disease, the author shows how much the modern world has been shaped by bacteria and viruses, whether it be dooming the Neanderthals, spreading Christianity, or turbocharging the Industrial Revolution. He is especially sobering about what next may await us, thanks to antibiotics, whose success has produced bacteria that are increasingly resistant to the available cures. Enlightened governments working in concert to improve health care around the world offer the best hope against the next pandemic. If you scoff, then you better stock up at Trader Joe’s and get a lifetime Netflix subscription.

In the 1920s, Oberstdorf was an especially picturesque town in Bavaria, a favorite holiday spot populated largely by Catholics but welcoming to all, as long as they could afford to vacation there. What Julia Boyd and Angelika Patel have done is nothing short of remarkable: they’ve documented in detail how villagers, at first slowly and then rapidly, came to embrace Nazism. Starting in the early 1930s, after Hitler came to power, the town changed bit by bit, from the music taught in its schools to a swastika placed on a church spire. When war did begin, the village was initially unaffected, but when the war started going badly for Germany, the number of soldiers from the village who died fighting rose dramatically, and refugees from Allied bombings flocked there. Instead of guilt, the villagers chose self-pity, and after the war they worked hard not to remember. A Village in the Third Reich is a compelling chronicle of how ordinary people can be swept up into a monstrous movement without attending mass rallies or worshipping Hitler but by going along with the national mood to preserve their quaint little town. Oberstdorf’s foolishness was as stunning as its scenery.

Irma, Pathogenesis, and A Village in the Third Reich are available at your local independent bookstore, on Bookshop, and on Amazon