In his 2019 autobiography Me, Elton John described Tony King — the promotional guru, dextrous rock fixer and friend to the stars — as somebody so flamboyant he “would have attracted attention in the middle of a Martian invasion”. Coming from John, a man who arrived at his 50th birthday party in a removal van to accommodate his planet-size Louis XIV wig, it was quite the compliment.

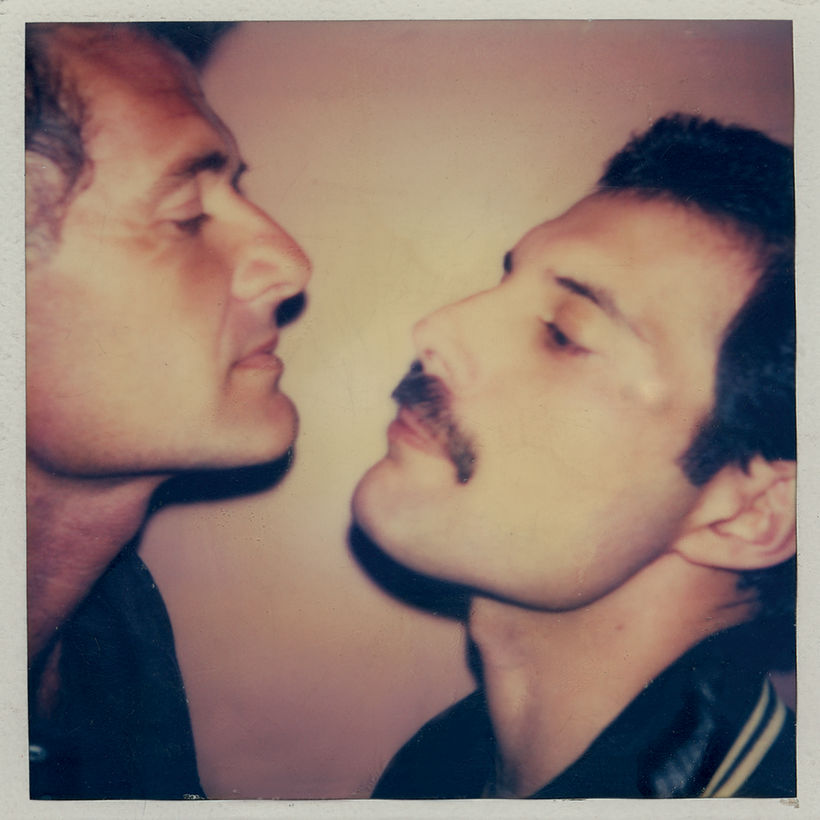

Yet The Tastemaker, King’s account of more than 60 years spent working with the A-listers — the Beatles, Freddie Mercury, the Rolling Stones — is not quite as showy as John’s tribute suggests. Names drop like feathers from a marabou cape, but King understands his place in this gilded world and knows how to balance irreverent entertainment with respectful discretion.