Daisy Hay’s new book is hugely engrossing, yet its hero, Joseph Johnson, is almost unknown today. He was a bookseller and publisher with a shop at 72, St Paul’s Churchyard, London, where in the tumultuous years before and after the French Revolution he gave weekly dinners to an assortment of writers and thinkers.

The fare was ample but not luxurious, typically a fish and meat course with boiled vegetables followed by rice pudding. Authors down on their luck were glad of a meal, but what attracted most of the guests was not the food but the brilliance of the talk. As if to stimulate their imaginations, a painting called The Nightmare by Johnson’s friend Henry Fuseli dominated the room, showing an incubus leering over a sleeping woman.

Among the guests were the men and women whose ideas and writings constituted the intellectual avant-garde of the Western world. They included William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the scientist and revolutionary political thinker Joseph Priestley, the anarchist philosopher William Godwin, author of Political Justice, the doctor, botanist and poet Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin, whose theory of evolution Erasmus partly prefigured, the scientist Benjamin Franklin, famed throughout Europe for his experiments with electricity, and the political activist Thomas Paine, whose Rights of Man defended the French Revolution against its critics.

Johnson also fostered groundbreaking advances in medicine and obstetrics, publishing works by Thomas Percival, Edward Rigby and others. William Blake came within Johnson’s orbit, too, although he was employed as an engraver, not a writer, and Johnson displayed Blake’s hand-printed volumes in his shopwindow.

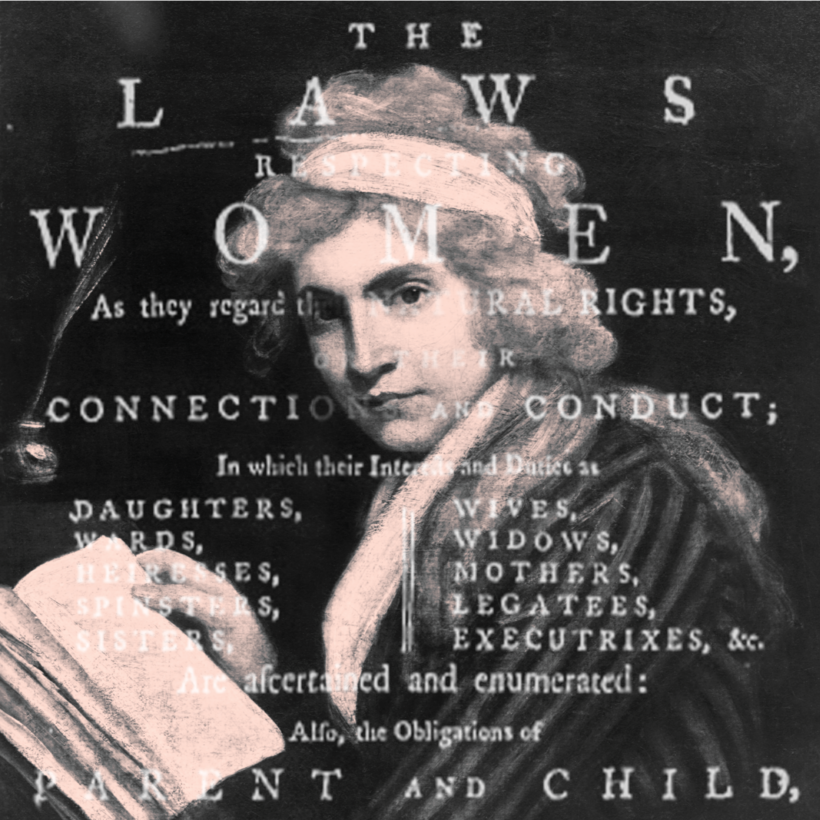

Johnson’s female guests were as remarkable as the men, if not more so. The star was Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published by Johnson in 1792, which argued for the educational and social equality of women. She was passionate and unstable, and twice attempted suicide. She had an illegitimate daughter by an American adventurer called Gilbert Imlay, and her relations with Johnson were very close, though not, Hay thinks, sexual. She married William Godwin and died giving birth to a daughter, Mary, who was to marry the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and, in 1818, publish Frankenstein.

Among the guests at Joseph Johnson’s dinners were the men and women whose ideas and writings constituted the intellectual avant-garde of the Western world.

Almost as brilliant as Wollstonecraft was Anna Barbauld, who went to revolutionary France in 1785 and helped to inspire Wordsworth and Coleridge, although they disengaged themselves from her extremism later. In her poem “Eighteen Hundred and Eleven,” as Hay might have mentioned, she prophesied that America would replace Britain as a world power and was ridiculed for it at the time.

Barbauld also gave thought, as almost no one had before, to encouraging early literacy by designing books for small children with extra-large type and few words per page. Another of Johnson’s female authors, Sarah Trimmer, was the first to design picture books for children, and the Anglo-Irish Maria Edgeworth, also a Johnson author, was one of the first writers of realistic children’s literature.

A constituent of the Johnson group’s thinking that earned the hostility of the established church was Unitarianism; that is, the belief that the Christian God is a single entity not a Trinity. Wollstonecraft, Priestley, Coleridge and Erasmus Darwin were Unitarians, as was Johnson, and he published the work of Theophilus Lindsey, who founded the first Unitarian church in England in Essex Street, near St Paul’s. To the authorities, dissenters, such as Unitarians, who preached or published their views were disturbers of the peace and should be silenced.

The first of Johnson’s circle to suffer was Joseph Priestley. An outspoken supporter of the French Revolution, he had moved to Birmingham as Unitarian minister where, in July 1791, a drunken mob, evidently with the connivance of the magistrates, burned down his home, destroying his library and his scientific equipment. He and his wife barely escaped with their lives, and fled to America, where Johnson faithfully continued to send him books.

A constituent of the Johnson group’s thinking that earned the hostility of the established church was Unitarianism; that is, the belief that the Christian God is a single entity not a Trinity.

Johnson attracted the attention of Pitt’s Tory government and its supporters by founding, in 1788, a monthly periodical called The Analytical Review as a forum for radical political and religious ideas. Its contributors disguised their identities by using only initials, often spurious, so some remain unknown, but they included Barbauld and Fuseli, and Wollstonecraft acted, in effect, as its editor. Conservatives countered with the Anti-Jacobin Review, which had a cover by James Gillray showing Truth holding her torch aloft while the monstrous figure of Jacobinism cowers in his cave.

Meanwhile government spies intensified their activities as events in France became more alarming. Wordsworth and Coleridge were spied on in rural Somerset and, in 1798, a spy walked into Johnson’s shop and bought a pamphlet by the controversialist Gilbert Wakefield, criticizing the government’s attitude to the French Revolution. Johnson had nothing to do with its publication, but he was sentenced to six months in prison just for selling it, and fined £50 (the equivalent, Hay points out, of several thousand pounds in today’s money).

His friends rallied round and ensured that he had comfortable accommodation at the prison in the coachman’s house, and he persisted with his weekly literary dinners in its parlor. But The Analytical Review ceased publication, so to that extent the conservatives triumphed. On his release he continued to encourage young authors, adding William Hazlitt, Humphry Davy and Thomas Malthus to his guest list. He died in 1809, aged 72. William Godwin paid tribute to him as a man of “generous, candid and liberal mind”, who was never heard to say “a weak or a foolish thing”.

Hay’s book has its longueurs, and some of its literary judgments are mind-boggling. She calls Charlotte Smith’s Beachy Head, for example, “one of the masterpieces of English Romantic poetry”. Its text is available online, so readers can judge for themselves. For all that, Dinner with Joseph Johnson is an exciting blend of ideas and personalities.

John Carey is a U.K.-based critic and professor of literature. He is the author of numerous books, including A Little History of Poetry, The Unexpected Professor, and What Good Are the Arts?