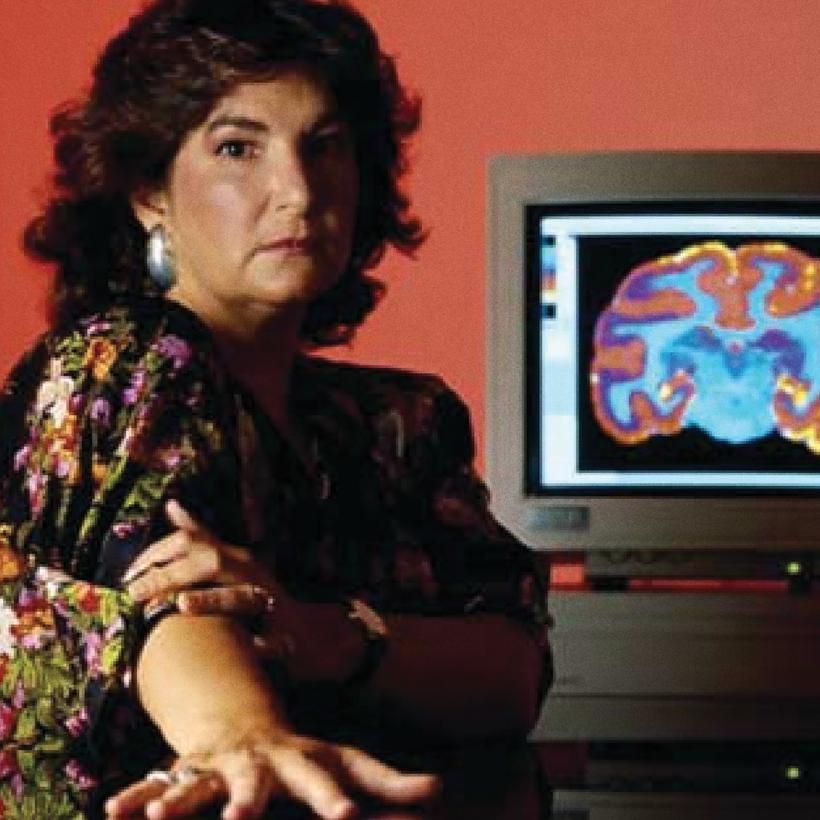

When I began research for my biography of Candace Pert, I was shocked to learn that both the opioid crisis and the mind-body movement originated with this one woman’s work. Indeed, her visionary medical research shaped history—for good and, inadvertently, for evil.

Pert was a 24-year-old graduate student in neuropharmacology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine when, in June 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a war on drugs. Across the nation, a spike in crime was increasingly blamed on an addiction epidemic. Heroin use had spread to the white middle class, and the news was riddled with stories of teenagers dying from overdoses.