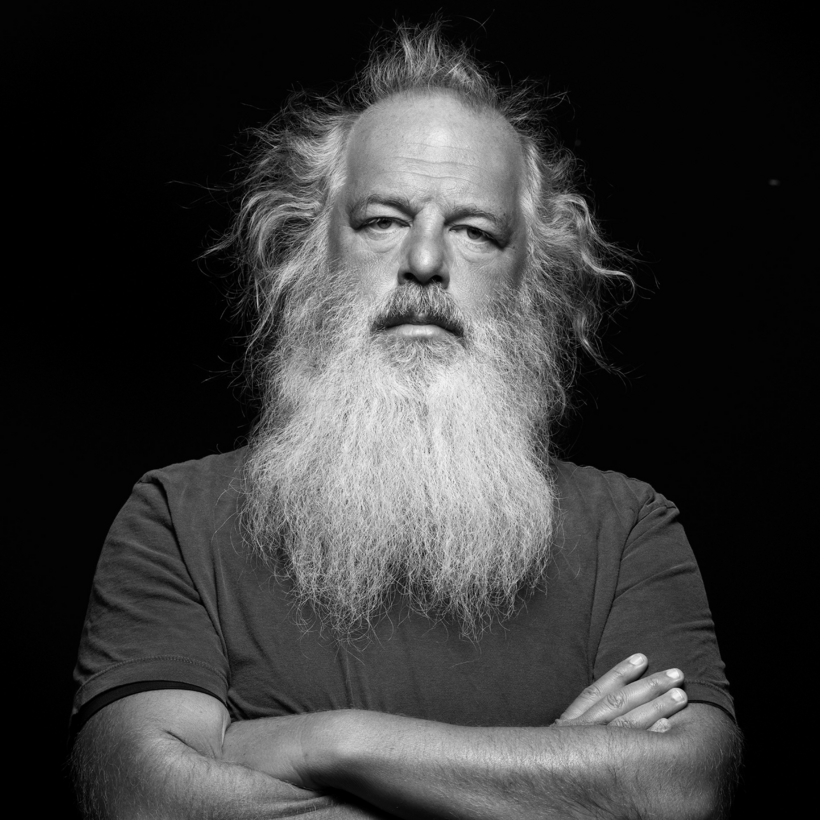

Grammy-garlanded pop singers, Oscar-scooping film stars and Olivier award-winning thesps can have an ambivalence about success that surprises us mere mortals. But the American record producer Rick Rubin’s response when the rap-rock trio Beastie Boys’ debut album, Licensed to Ill, which he co-produced, topped the US charts in 1986 takes some beating. “I remember one of the people we worked with called me,” Rubin, 59, recalls, “and said, ‘You have the No 1 album in the country, how does that feel?’ And I said, ‘I’ve never been more unhappy in my life.’”

Licensed to Ill went on to sell more than ten million copies in the US, a remarkable baptism for Rubin, who, in the decades since, has also produced or co-produced multimillion-selling monsters by Public Enemy, Slayer, Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Cult, System of a Down, Shakira, Johnny Cash, Tom Petty, Jay-Z, Adele and more.