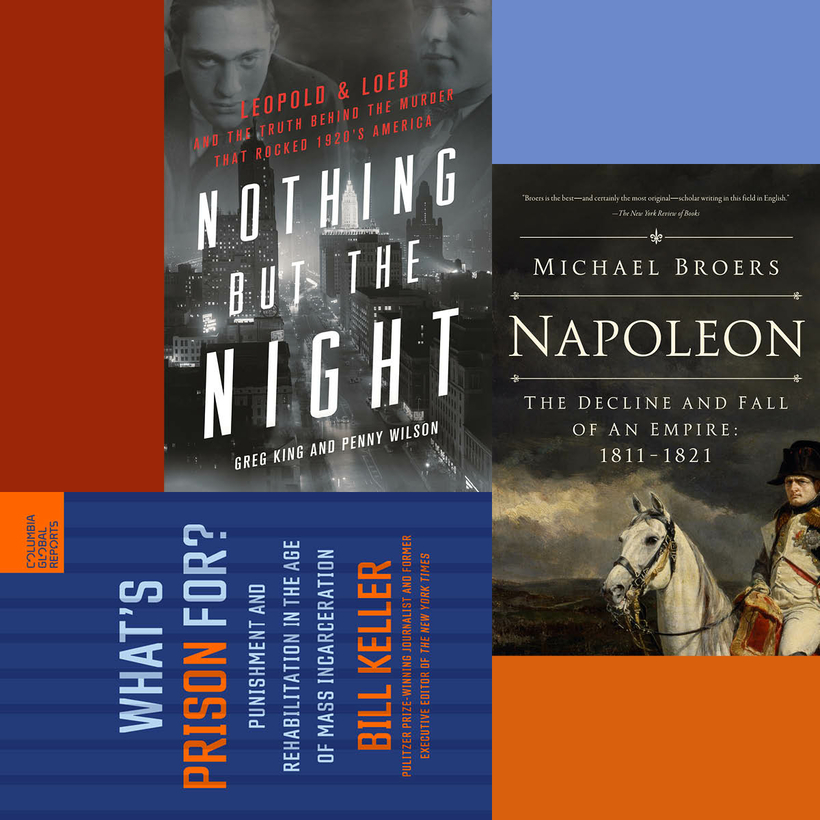

Almost 100 years ago, a pair of Chicago teenagers named Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb kidnapped and killed a 14-year-old boy named Bobby Franks. The murder transfixed the nation, partly because both killers came from wealthy families and were well educated, partly because they were lovers and seemed unrepentant in their effort to commit the perfect crime, and partly because the famed lawyer Clarence Darrow managed to save them from the death penalty. Loeb was killed in prison in 1936, while Leopold, who did finally profess remorse, was released in 1958 and died 13 years later.

The crime inspired both Rope, the 1948 film by Alfred Hitchcock, and the best-selling 1956 novel Compulsion, by Meyer Levin. Greg King and Penny Wilson do a masterful job of capturing the personalities of both the killers and the victim, the atmosphere of the times, the courtroom drama, and the final years of Leopold, who married the American widow of a Puerto Rican doctor and lived in an apartment in San Juan, where prominently displayed for visitors to see was a framed photo of Loeb.

This book, subtitled “The Decline and Fall of an Empire: 1811–1821,” is the third and final volume in Michael Broers’s biography of a man who ruled and terrorized much of Europe in the early part of the 19th century. Broers is doubly gifted as a storyteller, master of the telling detail as well as of the larger currents sweeping across that part of the world that both helped and hindered Napoleon. It is in this volume, of course, that Napoleon’s world falls apart and sees him exiled to St. Helena. It is a measure of the author’s skill that the reader feels a twinge of regret for the delusional despot and his last days on a barren rock.

Bill Keller has done something well nigh impossible: written a pithy, engaging book about prison reform, with flashes of wit and memorable quotes from both those incarcerated and their jailers. Nearly two million Americans are in prison, “a captive population [that] is disproportionately Black and brown,” and if America does not hold first place for imprisoning such a large number of people (who knows, really, how many are jailed in China?), it is up there.

Keller, who served as top editor at The New York Times for many years and then became the founding editor of the Marshall Project, the nonprofit covering the criminal-justice system, does not dwell on these statistics but instead deftly explores all the ways prisons could be better not at punishment but at rehabilitation. He argues that the potential for reform resides in so many of the prisoners themselves, if only we did a better job at tapping that potential, whether by hiring prison wardens with doctorates in criminology or by adapting aspects of the Norwegian prison model, where the great majority of inmates have jobs, attend schools, are allowed to vote, and are otherwise being prepared to rejoin society. Keller is refreshingly optimistic about the direction of prison reform, in ways small and large, and by book’s end you feel as invested in better prisons as if you yourself might do time someday.

Nothing but the Night and Napoleon are available at your local independent bookstore, on Bookshop, and on Amazon. What’s Prison For? will be available beginning October 4