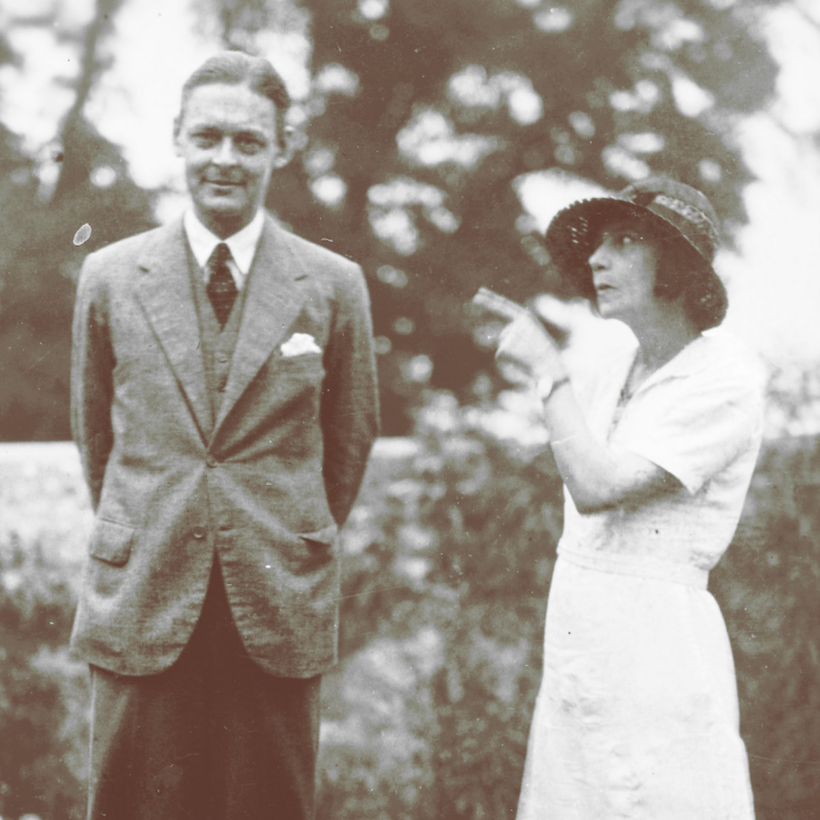

To many readers TS Eliot seems an austere and remote figure, hidden behind unintelligible poetry and intimidatingly erudite prose. So it is a pleasant surprise to find that in this whopping second (and final) volume of Robert Crawford’s biography, although due attention is paid to Eliot’s writing (and to his rampant racism and anti-Semitism), Eliot’s love life, or lack of it, is a big concern.

However, Vivien proved disgusting to him physically, and her constant, erratic demands drove him to distraction. Their tortured marriage was, he conceded, one of the reasons for the generally rather glum view of life taken in The Waste Land. It may be, too, that it was to get away from Vivien in the daytime that he stuck to his full-time job in Lloyds Bank, from which well-meaning friends wished to “free” him.