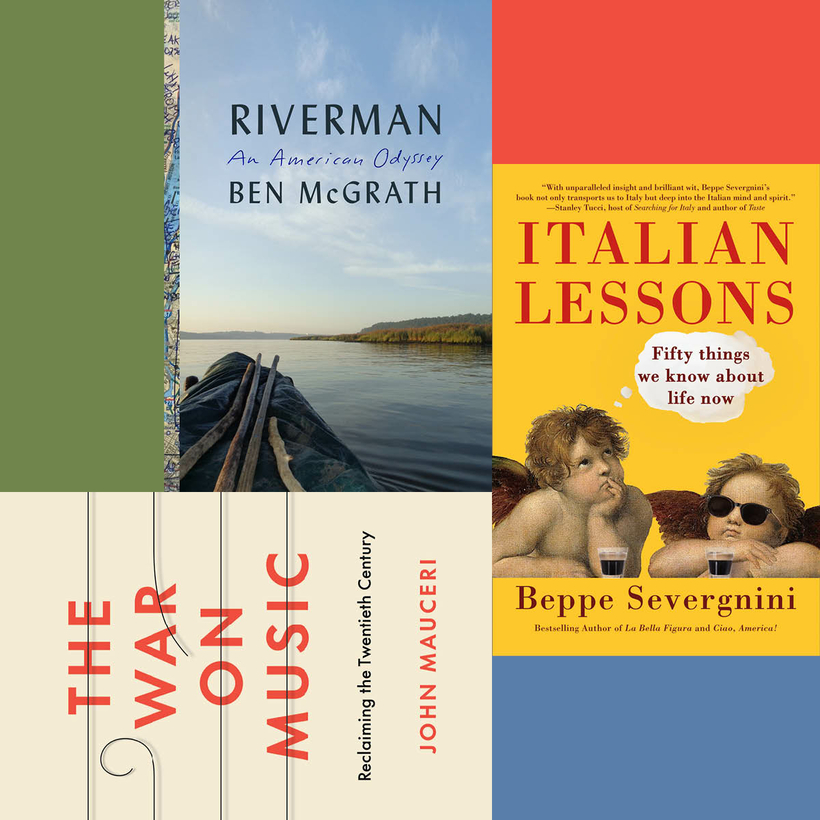

It was by chance that Ben McGrath met Richard Perry Conant, a wandering canoer, “with the complexion of a boiled lobster, to go with the build of a manatee,” who had lashed his boat near the author’s house on the Hudson River one weekend in 2014. Everything Conant told McGrath mesmerized him: his traversing hundreds of miles of river, his planning of trips so he could always check into a nearby V.A. hospital, his vivid encounter with a heron, his writing of a screenplay starring Bette Midler driving off a cliff (tentatively entitled “Drowning Mona”). McGrath wrote a short item about Conant for The New Yorker, and that was that.

Except three months later he got a call from a wildlife ranger in North Carolina who said they had found an abandoned red plastic canoe stuffed with possessions, including a piece of paper with his phone number on it. Conant had disappeared, and the ranger wondered if McGrath knew anything about him.

So began McGrath’s quest to fill in the blanks about his erstwhile friend, a quest helped by Conant’s siblings and the various people he had befriended in his travels. Journals and poems and paintings were found in lockers Conant had rented, and slowly McGrath pieced together the life of a man compassionate and friendly to all he met, a life of adventure and challenge that led him to find solace on the river. This astonishing narrative is part detective story, part remembrance, and wholly faithful to a decent man full of peculiarities. Conant’s body was never found, but McGrath did something better for readers: he discovered Dick Conant the man.

Just when it is safe enough to travel abroad again without quarantines comes Italian Lessons, subtitled “Fifty Things We Know About Life Now,” or, more precisely, Italian life. There is a reason why Italy remains a favorite travel destination, especially for Americans, and what better guide can we have than Beppe Severgnini, an editor at Corriere della Sera, the country’s largest daily newspaper. Take No. 23, entitled “Because Sardinia smells like patience.” “Sardinia is the oldest part of a very old country,” he writes, “the part of Italy where people live longest and talk least. Sardinia is Italy’s western balcony, the place where we sit to calm our anxieties.” Beautifully written and trenchant in observation, Italian Lessons is a delightful course open to any student who appreciates a good story, let alone 50 of them.

This book grapples with what constitutes good classical music by approaching the subject from a provocative angle: Why do we not play more often the music banned by Hitler, specifically Schoenberg, Korngold, Hindemith, and Weill? And why instead do we fall for so much of what John Mauceri calls the “institutional avant-garde,” typified by Helicopter String Quartet, by German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, with, yes, each player in a separate chopper? The reader may not agree with Mauceri’s analysis, but his writing is more exhilarating than any helicopter ride we have been on.

Riverman, Italian Lessons, and The War on Music are available at your local independent bookstore, on Bookshop, and on Amazon