In he spring of 2012, when the idea for True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson was a seedling, I covered an event at the Jackie Robinson Foundation. For much of the night, I talked with Joe Morgan at a small table away from the larger crowd. Morgan was the thrilling, parameter-shifting second baseman who was a standout player for the Cincinnati Reds—nicknamed “the Big Red Machine” for their dominant offense in the 1970s. His plaque has been up at the Baseball Hall of Fame since 1990. He died in 2020 at the age of 77.

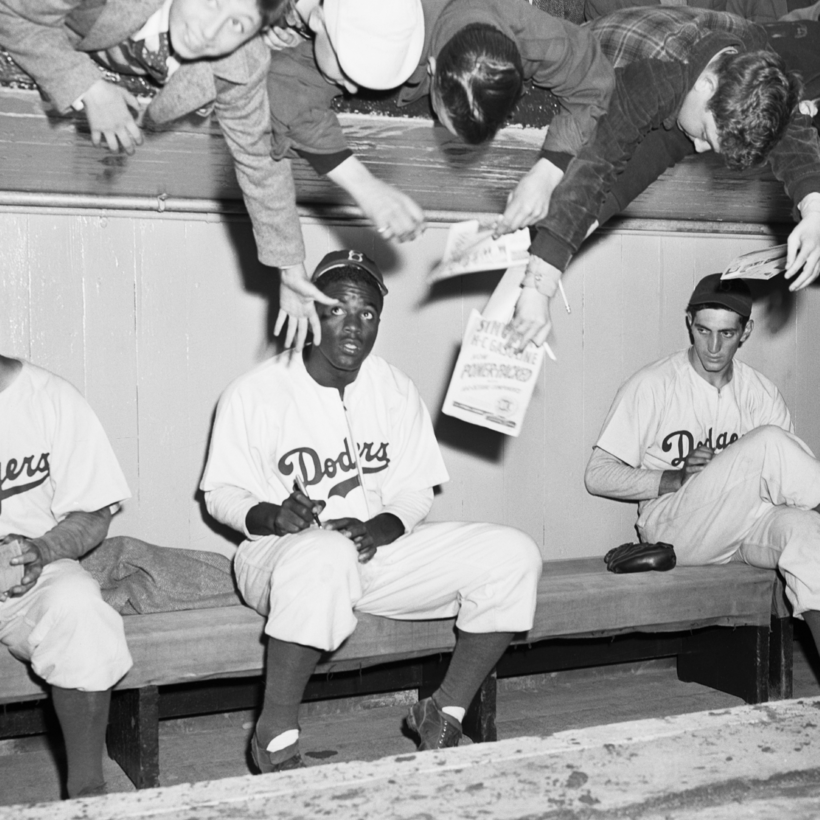

At the time of that event, Morgan had been working and volunteering on behalf of the Jackie Robinson Foundation for decades. He explained that, like Robinson, he grew up in California. He was three years old when Robinson began his revolutionary Dodgers career, in Brooklyn in 1947. At age 19, in 1963, Morgan broke into professional ball by playing for the Durham Bulls, a Class A minor-league team. On an early road trip with the team, he was subjected to segregation and verbal abuse.