In the final pages of George Eliot’s Middlemarch, the narrator, reflecting on the book’s heroine, Dorothea Brooke, wrote that “the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive,” and that “the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts.” In celebrating good bookstores, I found myself wondering if what is true of the effect of people on those around them might also be true of the effects of institutions on those around them.

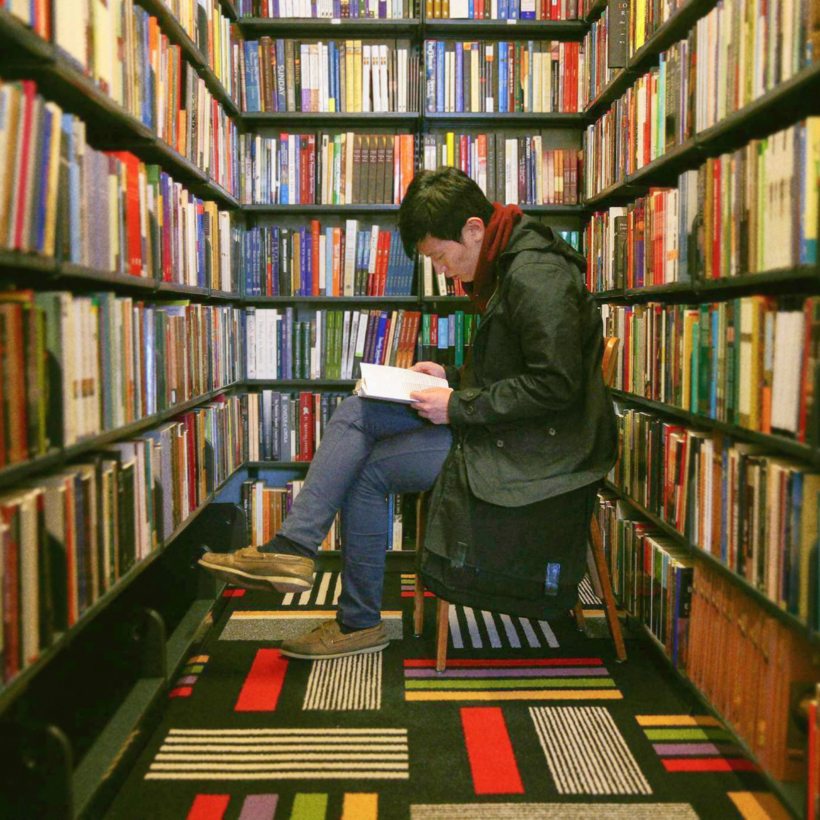

The Seminary Co-op Bookstore, in Chicago, is one of our country’s finest bookshops, and among its best-kept secrets. Its focus on books published by academic and small presses, on otherwise under-represented authors, and on backlist titles (books published more than two years prior) isn’t unique, but it is rare.