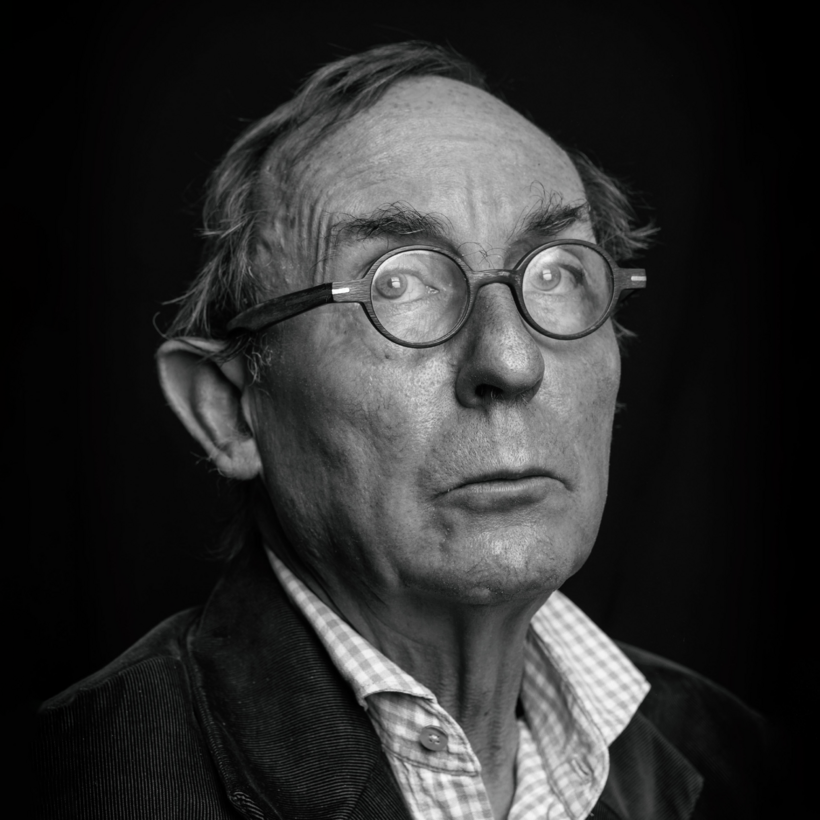

One word is conspicuously absent from the 312 pages of this autobiography: fogey. In the 1980s London media-land started to notice the existence of Young Fogeys—a cabal of writers and aesthetes in their twenties and thirties, typically dressed in formal clothes, riders of push-bikes and devotees of classical art and architecture—of whom AN (Andrew Norman) Wilson was the most visible exemplar. The cover of Confessions shows him in arch-fogey mode at 32, with his natty attire, midwife’s bicycle and meek demeanor—but this memoir, which takes us up to his mid-thirties, wants to demolish such an image. From the start Wilson presents himself as a shameless badass.

In Chapter 1 he describes his first wife, the Oxford academic Katherine Duncan-Jones, in the grip of dementia; her slide from sanity is signaled by her consumption of Co-op chardonnay and prawn sandwiches. And Wilson says: “I broke every vow and promise I made to that woman.” In Chapter 3 he’s lying in bed with a lover who, when asked by a friend, “Do you fancy Andrew?” had replied: “I can imagine tearing off his three-piece suit only to find another three-piece suit underneath.” Evidently she found something else. Wilson reports: “I was happy, as only very selfish young men can be happy.”