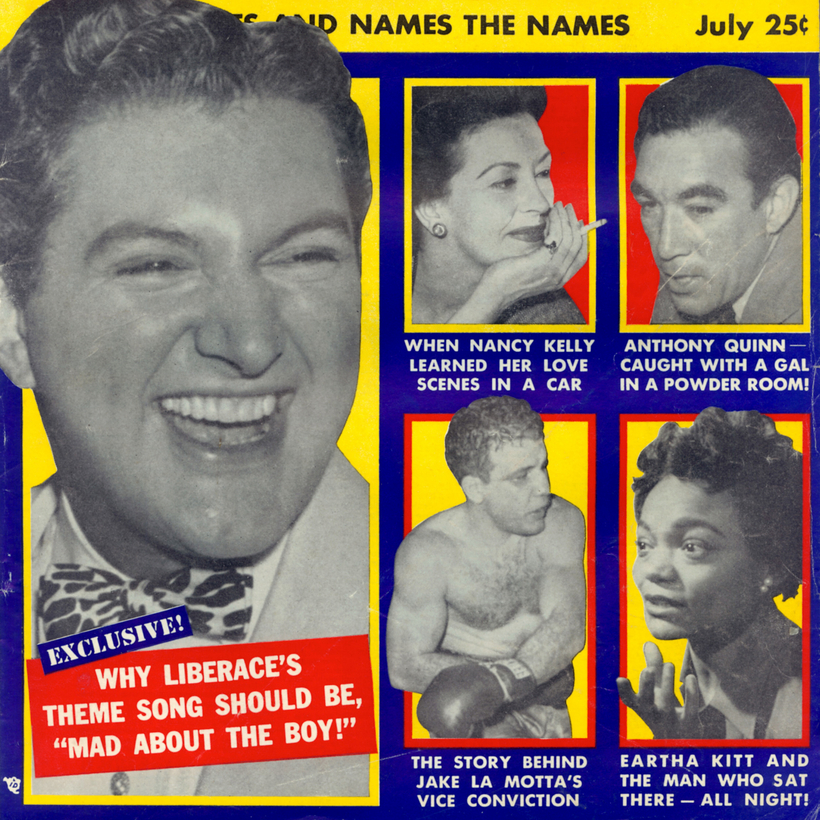

During much of the 20th century, journalists and editors of publications both mainstream and marginal faced the challenge of hiding information that they wanted their readers to find.

Social expectations, professional codes, and legal regulations limited how explicitly newspapers and magazines could address a variety of topics, including violence, religion, drug use, and race relations. Publishers wanted to cover these topics because they appealed to readers and sold issues, but doing so could also attract unwanted attention from government censors and libel attorneys—not to mention scandalize polite society.