The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer by Dean Jobb

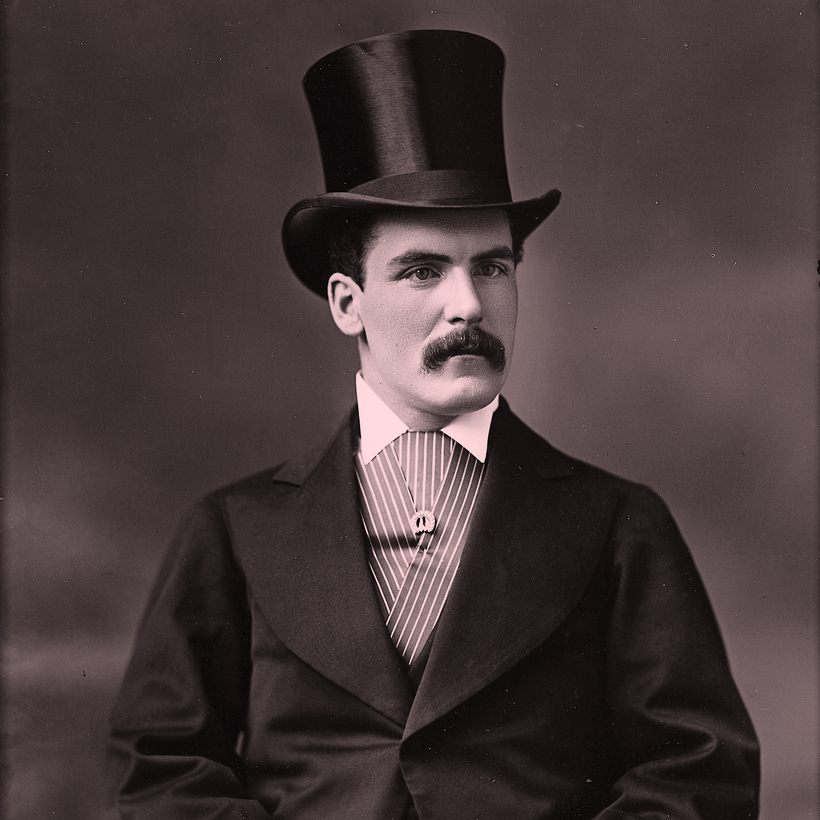

Thomas Neill Cream (1850-92), poisoner of at least nine women and one man, a serial killer before the term was coined, a doctor whom the News of the World dubbed “the greatest monster of iniquity the century has seen”? No, me neither.

Yet 5,000 people gathered outside Newgate’s high walls on the morning of his execution even though there was nothing to see. “It’s better hanging about out here,” said one of the ghouls, “than hanging up inside.” A waxwork of Dr Cream remained in the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussauds in London until 1968.