Ah, to live in the days when to get away from it all you could fly to the Tangier International Zone, at the very top of Africa and only 20 miles from Spain, and hang out with spies and smugglers, with Barbara Hutton (who would phone the U.S. consul to gripe about the taste of the Coca-Cola sold there) and Ian Fleming and Matisse and T. S. Eliot. (Now that’s a dinner party you won’t see mentioned in the New York Times feature “By the Book.”)

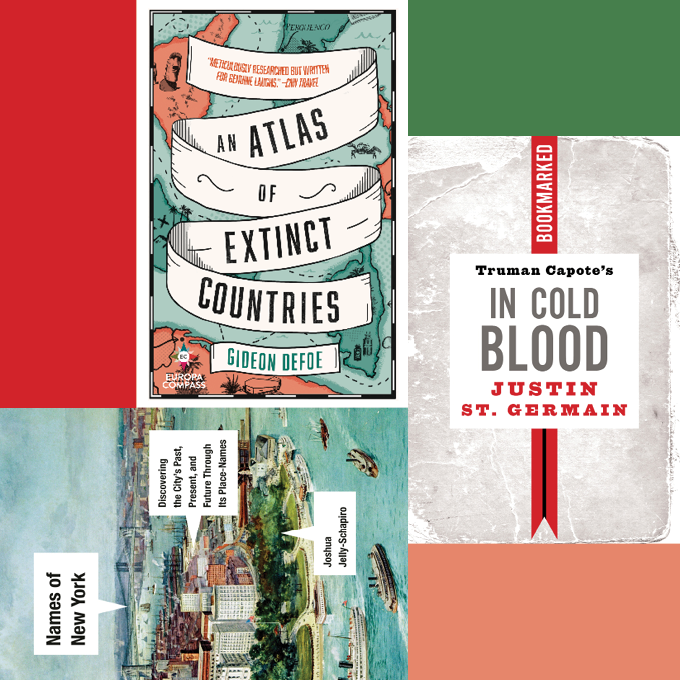

The zone, which lasted from 1924 until 1956, when it became part of Morocco, is one of 48 countries that no longer exist, all detailed in irreverent and rollicking style by Gideon Defoe. In what expired country was the currency cowrie shells? (Dahomey, now Benin.) Where was the Great Republic of Rough and Ready? (In California, and it lasted from April 7 to July 4, 1850, when its citizens discovered they could not buy booze in a neighboring town because they were now deemed foreigners and so they dissolved their nation.) And don’t forget the Free State of Bottleneck, accidentally created in 1919 when an imprecise rendering of occupied zones in Germany after World War I resulted in an orphaned population of 17,000. For four glorious years Bottleneck ruled, until France pocketed it.