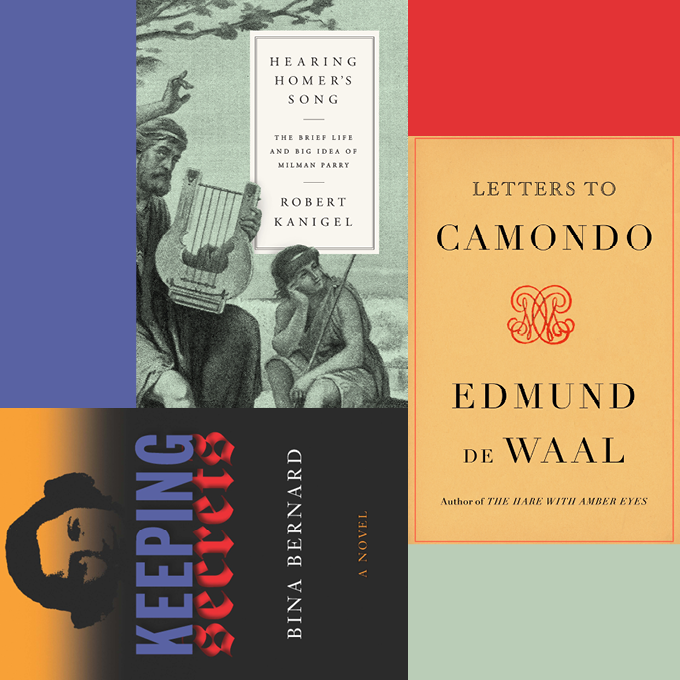

Until Milman Parry came along in the 1920s, Homer was considered the writer of The Iliad and The Odyssey, in the same sense as, say, Shakespeare had written his plays. Parry exploded that notion by showing that Homer’s epic poems had been composed orally, “becoming itself, in the act of singing or speaking.” Who exactly Homer was became irrelevant, since so much about the poetry relied on traditions that could not be tied to one person, unlike, say, the work of Virgil.

Robert Kanigel has turned Parry’s life into a remarkable epic of its own, from Parry’s humble beginnings as a druggist’s son to his academic prowess at Harvard, to his travels through Yugoslavia, to his mysterious death, by a gunshot wound in a Los Angeles hotel room in 1935, when he was just 33. Never has the world of dactylic hexameter been made to sound so dramatic.

Fans of Edmund de Waal’s captivating memoir The Hare with Amber Eyes are in for a different kind of treat: 50 imaginary letters written to the real-life Comte Moïse de Camondo, an art collector who lost his son in World War I and later left his house to the French government under the condition that nothing inside ever be changed. The result is part inquiry, part history, part philosophy, and wholly poignant and original. The Musée Nissim de Camondo is temporarily closed due to the pandemic (it’ll open next week), but fans of the TV show Lupin have already been there, since the grounds and the interiors were used as the home of Lupin’s wealthy antagonists, the Pellegrini family.

No child should ever judge a parent until the child becomes a parent, and perhaps not even then. Bina Bernard, a first-time novelist born in Poland who came to the U.S. with her parents, deftly weaves the immigrant experience into the suspenseful tale of a daughter’s return to Poland to investigate the life-and-death choices made by her family during World War II. Let those who judge …