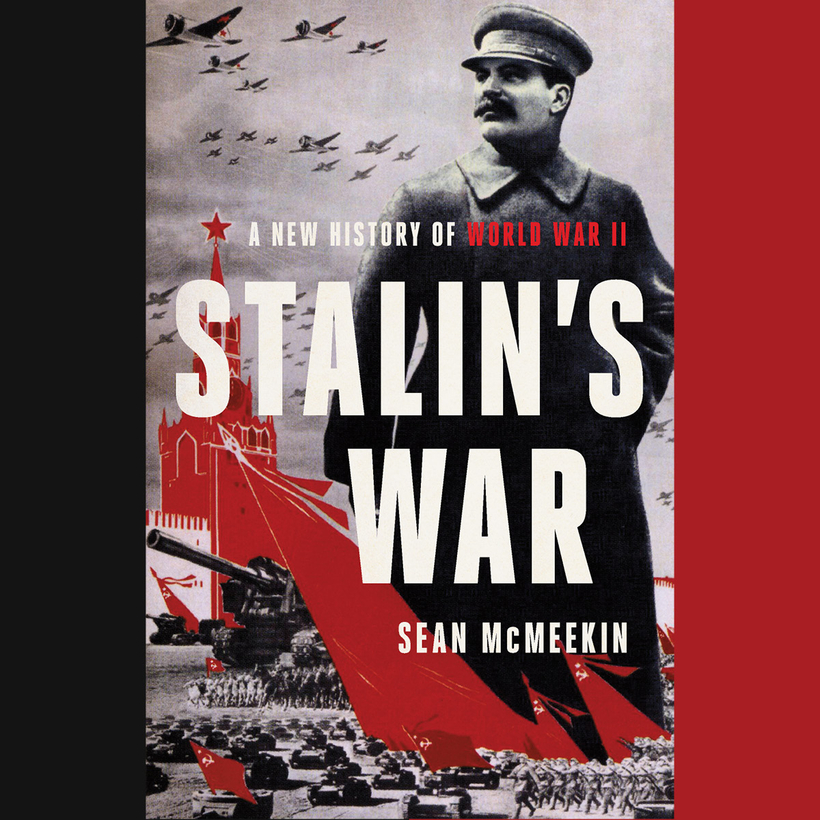

When I set out to research Stalin’s War, my history of the Second World War publishing later this month, I was expecting to find that Winston Churchill was more stubborn in resisting Soviet demands than U.S. president Roosevelt, the latter so famously solicitous of Stalin’s favor in everything from gargantuan Soviet Lend-Lease consignments to plans for Poland.

In general, this turned out to be true, although this is not saying much for Churchill, who also bent over backward to satisfy Soviet requests, from his impulsive gifting of 200 Hawker Hurricane pursuit planes pledged to defend Singapore to Stalin in the wake of the German invasion of the U.S.S.R. in June 1941, to pressuring Poland’s exile government in London to accept Stalin’s preferred Polish borders at the Moscow conference in October 1944.