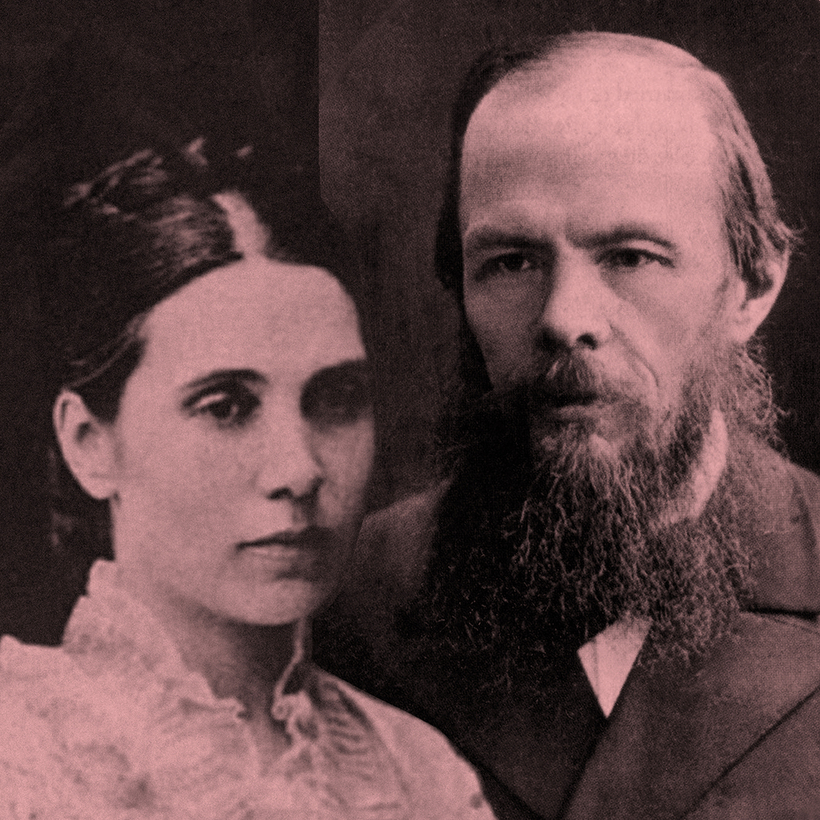

These days it is fashionable to treat Fyodor Dostoevsky as a kind of floating brain who spent all day at his desk pondering grand philosophical dilemmas, but in many ways his ideas were a direct by-product of a life filled with political and romantic intrigues. Perhaps the most intense of these was his affair with Polina Suslova, a brief, fiery relationship that would later inspire Martin Scorsese’s short film “Life Lessons.”

Having been arrested for advocating the emancipation of the serfs in 1849, Dostoevsky found himself living cheek by jowl with them in Siberia. Ten years later, he returned to St. Petersburg more convinced than ever that the country’s social unrest was a result of the intelligentsia being alienated from the common people. It must have seemed an extraordinary stroke of luck when he encountered Polina, the daughter of a freed serf who was now mixing among the student radicals. She was the living embodiment of Dostoevsky’s ideals, and she also happened to be beautiful.