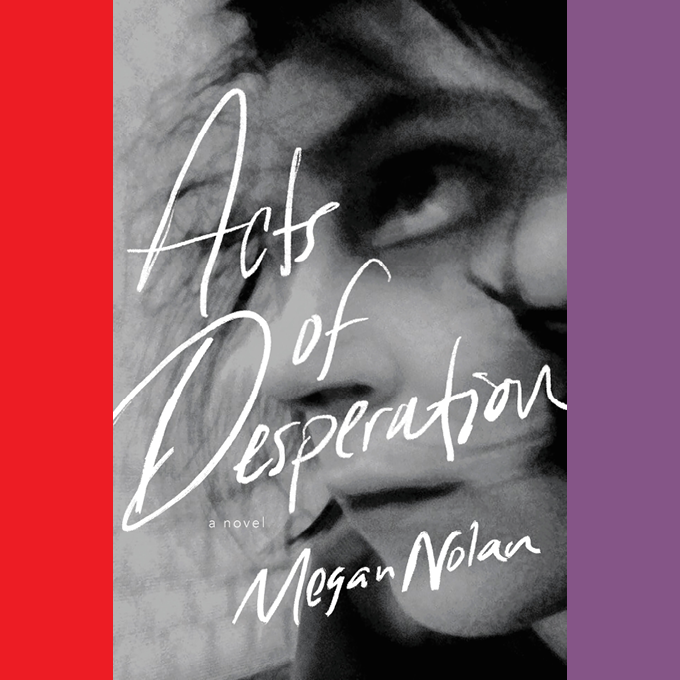

“How can I describe what happened to me without the word love?” the unnamed narrator asks in the opening pages of Megan Nolan’s excellent debut novel, Acts of Desperation. What happened between this man, who liked to smoke while he received oral sex, and this woman, who liked to lay on the floor while her lover circled her like a shark? Chronicling their obsessive, worshipful, ultimately hazardous love, the narrator performs an autopsy, with an eye to cause and motive.

She starts with the moment she first laid eyes on him, an art critic named Cirian, while looking for a bar at a gallery opening in Dublin: it might have been love at first sight, but then she quickly realizes that she’s seen him before, narrowly avoiding a cliché. The narrator is aware of her story’s dangerous proximity to the fairy tale. She was a romantic herself then, waiting tables, and waiting for her stars to align. “My understanding was that every action would lead me to where I ought to be,” she reflects, “and where I ought to be was in love.” She leaves her first date with Cirian knowing that “it didn’t matter to me how funny he was, or what he thought of me, or what books we had both read. I was in love with him from the beginning, and there wasn’t a thing he or anybody else could do to change it.” Her fate is sealed; the gods of love have struck. Or so she once believed.